Post by Return of the Thin Olive Duke on Apr 28, 2016 14:13:06 GMT -5

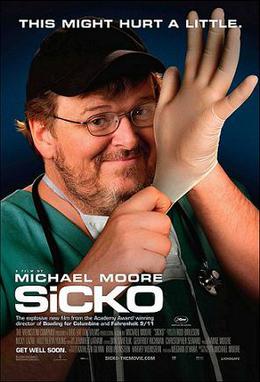

Sicko

Dir. Michael Moore

Premiered June 29, 2007

Michael Moore is a great filmmaker. In a time when documentaries were little seen, he stepped in front of the camera and became our friendly, funny guide, a format that blossomed in the 2000s through his own efforts as well as those of imitators like Morgan Spurlock. Yes, he’s made more bad movies than good ones. Yes, he’s often made it all about him. But no filmmaker has done more to bring documentaries into the mainstream of popular culture.

Even so, I’ve been taken aback of late by a growing number of people who have called 2007’s Sicko his greatest film. To be sure, Sicko lit a fire under the collective ass of the American left to start pushing for healthcare reform after over a decade with its tail between its legs, with actual if not total success, but when dealing with such blatant partisanship, it is often difficult to put aside political impact from cinematic quality.

Of all Michael Moore’s documentaries, Sicko is by far the most restrained. Moore himself doesn’t appear on screen for the first 45 minutes of the film, instead preferring to document the myriad ways in which the American people– the ones with health insurance, no less– have been defrauded by a for-profit system that outright refused to provide for them. A system in which administrators and even doctors were charged with denying coverage to people under bogus pretexts, burdening them with pain and often death (at the time 18,000 Americans died each year due to inability to pay for health treatments) in the name of profit.

This is horrifying, and much of the problem has not been fixed, but it’s interesting to look back to 2007, before the Great Recession, when allowing people to die for lack of funds was not only uncontroversial, but often viewed as a source of the nation’s moral fiber and work ethic. Healthcare was a privilege, not a right, deserved only by those who had earned it through gainful employment. So when Moore does step into the limelight, it is merely to point out that America is in fact alone in this fashion; that most of the developed world (to use Moore’s examples, Canada, the United Kingdom, France, and even pre-reproachment Cuba) has assumed a moral obligation to care for everyone, and that these services are neither as threadbare, draconian nor as, nor as conducive to the eruption of socialist enslavement than we have been led to believe. From there, things turn serious again, as Moore takes a group of betrayed citizens, among them volunteers who came to the rescue on the September 11 Attacks, to Cuba, to get access to basic medical care that their own country– my own country, the richest country in the world– does not see fit to give them.

If you’re looking for intellectual rigor, you won’t find it here. Hard numbers come up now and then, but Sicko is less concerned with making a practical argument, and more focused on the principle that we’re all in this together; that we all know what the problem is, and that all we really need is to abandon our political culture’s tacit social darwinism and have the balls to stand up for what’s morally right.

In my sympathies, I am biased. Last week, I got a free medication refill that would ten years ago have cost me $650. I am a beneficiary of Medi-Cal, the free government-run healthcare program implemented by the increasingly nationalistic state of California, which was expanded under the 2009 Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare. And while Obamacare was an act of cowardly pre-emptive compromise, with a filibuster-proof majority in the Senate, it has done a lot of good, changed a lot of minds (as long as you don’t call it “Obamacare”), and is probably something that Sicko helped press the government to do. But is it Michael Moore’s best film?

No. In spite of its influence, its impact, and its relative lack of ego, Sicko never quite matches the excellent pacing, sarcastic wit, or unfolding horror of Moore’s debut, Roger and Me (though it does still have all those things). But it is a close second, and while it may remain in the shadow of Bowling for Columbine and Fahrenheit 9/11, it is far better than either and, in hindsight, far more worthy of your time.

Additional Notes

Ratatouille and Sicko premiered June 29 alongside Evening, a star-studded, critically reviled attempt at prestige drama.

Next Time: The Best (and Worst) of 2007 (So Far)

Dir. Michael Moore

Premiered June 29, 2007

Michael Moore is a great filmmaker. In a time when documentaries were little seen, he stepped in front of the camera and became our friendly, funny guide, a format that blossomed in the 2000s through his own efforts as well as those of imitators like Morgan Spurlock. Yes, he’s made more bad movies than good ones. Yes, he’s often made it all about him. But no filmmaker has done more to bring documentaries into the mainstream of popular culture.

Even so, I’ve been taken aback of late by a growing number of people who have called 2007’s Sicko his greatest film. To be sure, Sicko lit a fire under the collective ass of the American left to start pushing for healthcare reform after over a decade with its tail between its legs, with actual if not total success, but when dealing with such blatant partisanship, it is often difficult to put aside political impact from cinematic quality.

Of all Michael Moore’s documentaries, Sicko is by far the most restrained. Moore himself doesn’t appear on screen for the first 45 minutes of the film, instead preferring to document the myriad ways in which the American people– the ones with health insurance, no less– have been defrauded by a for-profit system that outright refused to provide for them. A system in which administrators and even doctors were charged with denying coverage to people under bogus pretexts, burdening them with pain and often death (at the time 18,000 Americans died each year due to inability to pay for health treatments) in the name of profit.

This is horrifying, and much of the problem has not been fixed, but it’s interesting to look back to 2007, before the Great Recession, when allowing people to die for lack of funds was not only uncontroversial, but often viewed as a source of the nation’s moral fiber and work ethic. Healthcare was a privilege, not a right, deserved only by those who had earned it through gainful employment. So when Moore does step into the limelight, it is merely to point out that America is in fact alone in this fashion; that most of the developed world (to use Moore’s examples, Canada, the United Kingdom, France, and even pre-reproachment Cuba) has assumed a moral obligation to care for everyone, and that these services are neither as threadbare, draconian nor as, nor as conducive to the eruption of socialist enslavement than we have been led to believe. From there, things turn serious again, as Moore takes a group of betrayed citizens, among them volunteers who came to the rescue on the September 11 Attacks, to Cuba, to get access to basic medical care that their own country– my own country, the richest country in the world– does not see fit to give them.

If you’re looking for intellectual rigor, you won’t find it here. Hard numbers come up now and then, but Sicko is less concerned with making a practical argument, and more focused on the principle that we’re all in this together; that we all know what the problem is, and that all we really need is to abandon our political culture’s tacit social darwinism and have the balls to stand up for what’s morally right.

In my sympathies, I am biased. Last week, I got a free medication refill that would ten years ago have cost me $650. I am a beneficiary of Medi-Cal, the free government-run healthcare program implemented by the increasingly nationalistic state of California, which was expanded under the 2009 Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare. And while Obamacare was an act of cowardly pre-emptive compromise, with a filibuster-proof majority in the Senate, it has done a lot of good, changed a lot of minds (as long as you don’t call it “Obamacare”), and is probably something that Sicko helped press the government to do. But is it Michael Moore’s best film?

No. In spite of its influence, its impact, and its relative lack of ego, Sicko never quite matches the excellent pacing, sarcastic wit, or unfolding horror of Moore’s debut, Roger and Me (though it does still have all those things). But it is a close second, and while it may remain in the shadow of Bowling for Columbine and Fahrenheit 9/11, it is far better than either and, in hindsight, far more worthy of your time.

Additional Notes

- Ratatouille made me miss Paris; Sicko made me miss London.

- As far as interview subjects are concerned, the Sicko’s unsung hero is the late Tony Benn, former member of the British Parliament, many-time cabinet minister, and an unapologetic collectivist in the age of New Labour. He is by far the most articulate voice for the collective agreement that leads other countries to provide healthcare for all, and is just a joy to listen to. However, if his musings on Margaret Thatcher are to be believed, David Cameron is indeed much worse.

- My biggest problem is Moore’s characterization of the origins of the American health system, positing it as a devious calculation by Richard Nixon. In fact, the for-profit model is rooted in the need for companies to attract workers during wartime labor shortages, which should explain right there why it doesn’t work.

Ratatouille and Sicko premiered June 29 alongside Evening, a star-studded, critically reviled attempt at prestige drama.

Next Time: The Best (and Worst) of 2007 (So Far)