Deleted

Deleted Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by Deleted on Dec 23, 2016 22:34:05 GMT -5

Joe Somebody? Why? Please just let 2001 die in peace. I do like Jimmy Neutron though, more so the TV series than the movie. It is a premise that is perfect for a tv series. I was surprised at how long inbetween the movie and tv show was though. I think like three years. Have you actually seen Joe Somebody? It was a flop. And spoiler alert, there's basically only one good movie left for me to review. But it's a really good one. I have, when it first premiered on HBO. Which weirdly enough was around the time big trouble was on PPV, which I liked. And also had Tim Allen and Patrick Warburton. I did not care for Joe Somebody though. |

|

Deleted

Deleted Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by Deleted on Dec 23, 2016 22:35:37 GMT -5

I went to look at the list again, how is there still 5 fucking movies? 2001 should havr just ended at LOTR or Jimmmy Neutron.

|

|

|

|

Post by Return of the Thin Olive Duke on Dec 24, 2016 12:08:55 GMT -5

Joe Somebody

Dir. John Pasquin

Premiered December 21, 2001

The display was in every theater: a 3D print cutout of Tim Allen, in a shirt and tie, briefcase in hand as he stands astride his “reserved” parking lot. The banner surrounding this tableau: “Joe Somebody.” Never in my life had a film seemed so proud to be generic.

Joe Scheffer (Tim Allen) is a nebbishy, recently divorced A/V specialist at a pharmaceutical company. Because he’s a tech guy, he’s often overlooked by his coworkers. But that changes when arrogant salesman Mark McKinney (Patrick Warburton) steals Joe’s reserved parking space and publicly punches him over it, humiliating Joe in front of his colleagues and his daughter Natalie (Hayden Panettiere) on Bring Your Daughter to Work Day, one of those things which barely exist in real life but which popular culture takes for granted.

Despondent and unwilling to return to work, Joe is approached by corporate wellness coordinator Meg (Julie Bowen), who has taken a possibly-romantic interest in Joe while she is pursued by alcoholic company executive Jeremy (Greg Germann). However, Meg is horrified to discover that her kind words have inspired Joe to learn martial arts (with the help of a former B-movie star played by Jim Belushi) so that he can exact physical revenge on the bully McKinney– a plan that makes him the most popular guy in the office. Joe’s newfound confidence even earns him a promotion, but it also alienates Natalie, who is struggling in school. And Meg discovers that the promotion is a sham intended by Jeremy to placate Joe before firing him and watching McKinney kick his ass.

Joe Somebody is confusing and confused. Never mind dialogue like “She’s on the roof. I’m an 82-year-old man, she’s a 31-year-old woman. I know.” Virtually nothing in this ostensible comedy film is played for laughs. The script, cinematography, acting, and score bounce around between feel-good weepy, frathouse comedy, family-friendly romp, and corporate thriller; the tone is ever-changing and constantly bewildering, and I often had difficulty understanding what was going on. I certainly can’t imagine who the intended audience was. McKinney, the ostensible villain of the film, virtually disappears after the first act, and ultimately has no impact on the story as corporate puppetmaster Jeremy takes his place as the irredeemable baddie.

While Joe Somebody isn’t a very interesting idea for a film, it’s not a bad one either, at least not until the weird Pelican Brief shit, or two other subplots I won’t even bother mentioning as I’m not clear what was going on with either of them. Were it not Jim Belushi, I would have gladly preferred a small comedy about an ersatz Steven Segal making a new friend. But I struggle to grasp what this film was ever trying to do.

Signs This Was Made in 2001

- You know how Office Space portrayed the tech-fueled white-collar boom of the late 1990s as a meaningless bureaucratic abstraction that passively discouraged people from taking an active interest in their own work? Joe Somebody tries to put a positive spin on the same idea: workers at STARKe pharmaceuticals are lavishly endowed with the kind of perks typically only seen at Google, and it’s treated as perfectly commonplace.

- Joe joins his coworkers in a Karaoke rendition of the Backstreet Boys’ “Larger than Life.”

- The film is set in Minnesota and features a cameo by Governor Jesse Ventura at a Timberwolves game.

Additional Notes

Just like “Meredith Baxter-Dimly” in Bratz: the Movie, I have no idea if or why the character of Mark McKinney was named after the actor of the same name.

How Did It Do?

Joe Somebody earned a paltry $24 million against a $38 million budget, a feat as unusual in December 2001 as it was to make a profit in the preceding three months. The movie also received 21% on RottenTomatoes, with most critics declaring it trite and directionless. Richard Roeper agreed with me about the martial arts subplot being a potentially good idea for a movie.

Joe Somebody is symptomatic of bad comedies of this era in one particular way. Whereas most sub-par movies of 2001 were ungodly boring, comedies seemed to think that cramming several movies’ worth of plot into a 90-minute film would save it (these days, the thinking is to make the movie too long, because Knocked Up was too long). Joe Somebody is also symptomatic of a long line of movies in 2001 where the plot is driven entirely by one character’s desire for attention (see also: Battlefield Earth). It’s easy to plot a film this way because the characters can do any stupid thing, but it’s supremely uncompelling, and not at all becoming in the renewed patriotism of autumn 2001.

Next Time: The Majestic

|

|

|

|

Post by Return of the Thin Olive Duke on Dec 25, 2016 12:52:02 GMT -5

The Majestic

Dir. Frank Darabont

Premiered December 21, 2001

In one scene in Frank Darabont’s The Majestic, screenwriter Peter Appleton (Jim Carrey) rejects an excessively schmaltzy alteration to his script as “the dumbest thing I’ve ever heard.” This movie is one to talk.

A rising talent in 1951 Hollywood, Appleton seems to have it all: his first screenplay has been produced, his glamorous girlfriend (Amanda Detmer) is set to become a star, and he’s just getting started on a meatier script in the vein of How Green Was My Valley– until the House Un-American Activities Committee gets in his way. Blacklisted when the script is mistaken for Communist propaganda, Appleton goes on a drunken sojourn up the coast resulting in a car accident that gives him amnesia.

Waking up on the beach, Appleton has no idea who he is, but the residents of the nearby town of Lawson believe him to be Luke Trimble, the town’s favorite son who went missing in action in the Second World War. Most overjoyed is Luke’s elderly father (Martin Landau), whose love for his son drives him to reopen his business, the Majestic movie theater. “Luke” struggles to adjust to life in town, which seems to have spent the better part of a decade lying in wait for his return, and sparks begin to fly when he “reconnects” with his idealistic lawyer fiancée (Laurie Holden). But when Appleton’s disappearance has the U.S. Government convinced he’s a spy, the F.B.I. comes looking.

When I say “lying in wait” and “favorite son,” I mean it. Even as late as 1951, the business owners of Lawson still display their many gold stars from World War II. Screenwriter Michael Sloane could easily have changed the conflict to the Korean War and thus not needed to account for the years in between– my mother, who was born during said war, had the same thought– but there’s a reason it’s called “The Forgotten War,” as Sloane seems totally unaware that it ever happened. Luke, meanwhile, is not only a war hero, but the captain of his high school football team and an accomplished pianist. Whether he also walked on water is not said. And every word of exposition is delivered with the folksy conviction of players in a local production of Our Town.

With its Hollywood-adjacent historical setting, comfortably dated politics, tacked-on courtroom soliloquy, and a comedic star looking to make good, the transparent pandering for Oscar Glory is impossible to ignore. I’ve never seen a film slobber so indelicately over the magic of filmmaking, in theory if not in practice; it even throws in a fuck-you to television. And it’s all the more pathetic from a director with as many previous accolades as Frank Darabont (The Shawshank Redemption, The Green Mile).

Darabont was supposedly attempting to recapture the magic of Frank Capra, but does so in such a way that makes me wonder how many of Capra’s films he’s seen. Certainly the resulting movie is never as pointed or as deliberate as It Happened One Night, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, or It’s a Wonderful Life. The Majestic is not so much Capraesque as it is reminiscent of Dick & Jane, written at about the same grade level, and not even Carrey’s boyish charm and refreshing restraint can save the experience.

Additional Notes

Somewhat fun is Peter’s movie at the beginning, in which Bruce Campbell plays a swashbuckling adventurer, and the villain conks him on the head with the idol from the beginning of Raiders of the Lost Ark. That’s the only place in this film where the magic of movies really comes through. Partly because of the enjoyment I got just from that, I think the Coen Brothers were on to something with Hail, Caesar!, even if many critics don’t yet see it.

How Did It Do?

The Majestic bombed critically and commercially, earning $37.3 million against a $72 million budget and a 42% rating on RottenTomatoes.

The film’s most high-profile defender was Roger Ebert, whose reviews at the time evince clear signs of post-traumatic stress from the attacks, praising the film’s peaceful defense of American values and our way of life. If you couldn’t already tell, I respectfully disagree with the late critic. I take no issue with the patriotism displayed in the film, but such displays are totally unmotivated. The film speaks highly of sacrifice and service, but only in the past-tense. It claims to celebrate Hollywood, but the act of filmmaking is curiously absent. It makes a heartfelt defense of the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment, but freedom of speech is never seen in action. The Majestic is a great big eye-roll, a curiously directionless film that wants to be important, but never makes a real attempt to be so, and compensates with a dousing of treacle.

Next Time: Ali

|

|

|

|

Post by Return of the Thin Olive Duke on Dec 26, 2016 14:01:15 GMT -5

Ali

Dir. Michael Mann

Premiered December 25, 2001

Doing this project, it’s been interesting how many films have tied in to recent events in film and the wider world. In June of this year, the world lost Muhammad Ali, an international icon and one of the most recognized athletes in the world. And while I’ve been hard on biopics in the past, I had higher than usual hopes for Ali with Michael Mann behind the camera. Unfortunately, and bizarrely for a film about a man creating his own identity, it struggles to find purpose.

Ali covers a period of nine years in the titular boxer’s life, from his surprise defeat of Sonny Liston in 1965 to the Kinshasa “Rumble in the Jungle” against George Foreman in 1974. In between, Ali (Will Smith) struggles to be recognized by the name he has taken on, clashes with his father (Giancarlo Esposito), manager (Jamie Foxx), and various wives (Jada Pinkett-Smith, Nona Gaye, and Veronica Porché); takes on the U.S. government with his refusal to serve in the Vietnam War, and forms a belligerent friendship with broadcaster Howard Cosell (Jon Voight).

Mann unusually brings his trademark cinema verité style to this prestige biopic, but I like it here; it’s a refreshingly immediate departure from the staid setpieces usually found in movies like this. This anachronism of presentation pervades the film and briefly made me forget I was watching such overt Oscar Bait; specifically whenever Smith brought Ali’s signature grace and power into the ring.

Any other time, however, the film is plodding and aimless. The bulk of what may be called the first act concerns Ali’s relationship with Malcolm X (Mario Van Peebles), depicted in such a way that practically begs to stand in the shadow of Spike Lee’s Malcolm X. Around the same time, there is a subplot that is never explained and goes nowhere concerning U.S. government surveillance of Ali at the same time they are supporting Zairean dicator Mobutu (said dictator does become relevant later, but his inclusion early in the film is particularly pointless). Ali himself is inconsistently written; at times, Smith gets to play him as the notorious braggart of his younger days; at others he is strangely taciturn and passive. And while this is only a problem in retrospect, Jada Pinkett-Smith’s involvement as Ali’s first wife, Sonji Roi, is an uncomfortable reminder of everything that is wrong with Smith’s career since.

And that’s what bugs me most about the film. Most of it is forgettable, but the mercenary pandering for awards is not. Strangely for a film about such a game-changing figure, Ali still strains to make its story seem somehow more game-changing, such as the aforementioned Mobutu digression, and the briefest of flashbacks to Ali’s childhood reading news stories about the horrors committed against blacks in the Deep South– none of which ties into anything else.

Even before, the media hype was above and beyond. I distinctly remember the Smiths and Ali himself promoting the film on Oprah; Ali hindered by his recent stroke while Jada Pinkett-Smith yammered on bizarrely about her children and some other man beside her husband whom she maintained was part of “our circle.” It was disconcerting. Ali wanted to be the Movie of the Year. Sadly, it was little more than a good-looking Movie of the Week.

Additional Notes

I thought it at the time; I’m thinking it now: does anyone else find Will Smith unrecognizable without his mustache?

How Did It Do?

Would you believe Ali had the highest budget of any film released in December 2001? It cost $107 million; more than Black Hawk Down. More than Fellowship. More than all but three films I’ve covered for this project. So of course it flopped, grossing only $87.7 million. The film got a respectable 67% on RottenTomatoes, and Smith and Voight got Oscar nominations, but no wins. Michael Mann, justifiably unhappy with the studio’s final cut, later released his own version. Mann, then best known as the creator of the hit 1980s TV show Miami Vice and director of The Last of the Mohicans and Heat, later found awards success with the far less pandering Collateral.

Despite Will Smith’s iconic charm, the years have not been kindest to his career. He never starred in another film as beloved as 1997’s Men in Black, and most attempts to replicate his turn in that film were received coolly at best. He’s since become notorious for his flagrant nepotism, flirtations with Scientology, and furtive, increasingly desperate attempts at Oscar Glory, culminating in this year’s supremely ridiculous Collateral Beauty.

Next Time: Kate & Leopold

|

|

|

|

Post by Desert Dweller on Dec 27, 2016 1:08:17 GMT -5

Hey, at least I have heard of "The Majestic" and "Ali".

I am still shocked to realize how many of these films I have never heard of. "Joe Somebody"? I don't even remember seeing that 3D cutout in the theatre. Surely it was there when we went to see LOTR, but it obviously didn't make an impression on me.

I think I remember seeing one scene from "Kate and Leopold" on tv once. Maybe?

|

|

dLᵒ

Prolific Poster   𝓐𝓻𝓮 𝓦𝓮 𝓒𝓸𝓸𝓵 𝓨𝓮𝓽?

𝓐𝓻𝓮 𝓦𝓮 𝓒𝓸𝓸𝓵 𝓨𝓮𝓽?

Posts: 4,533

|

Post by dLᵒ on Dec 27, 2016 2:15:32 GMT -5

I think I remember seeing one scene from "Kate and Leopold" on tv once. Maybe? |

|

|

|

Post by Return of the Thin Olive Duke on Dec 27, 2016 15:05:42 GMT -5

Kate & Leopold

Dir. James Mangold

Premiered December 25, 2001

Just as my 12-year-old self had vaguely wanted to see K-PAX for the promise of aliens, I secretly harbored a desire to see Kate and Leopold for the promise of time travel. In both cases, I was better off seeing neither.

The film opens in 1876, where Leopold, Duke of Albany (Hugh Jackman) is living with his uncle and looking for a wealthy young American girl to marry and thus rescue his family’s finances. Faced with the prospect of marrying the dowdy Kristen Schaal, he retreats to his study, where he finds an intruder named Stuart (Liev Schreiber) who claims to come from the future. Laughing this off, Leopold chases Stuart up and off the unfinished Brooklyn Bridge, falling with him into the East River...and into 2001.

Believe it or not, this is the setup for a romantic comedy starring Meg Ryan.

Ryan plays Kate McKay, and unfulfilled Madison Avenue ad woman (don’t worry, the film has no idea how the ad industry works, nor how old it is) whose relationship with the time-travel-obsessed Stuart has reached its breaking point. Stuart, you must understand, is inadequate. We never find out why, though; instead Stuart is tortuously kept out of the movie until the very end by an avalanche of contrivance. Leopold, you see, is the inventor of the elevator, an achievement stolen from him by his treacherous valet Otis (bangs head against history textbook), and with Leopold in the present, the world’s elevators have vanished, sending Stuart down an empty shaft, breaking his leg, and landing him in a hospital where he’s apparently not allowed to make phone calls. Eventually, he is sent to an insane asylum because talking about time travel is apparently a perfectly scientific way to diagnose schizophrenia.

With Stuart mysteriously missing, and no one seeming to care, Leopold instantly charms the people who wander through the unlocked window of his New York apartment, including Kate, her squirrelly actor brother (Breckin Meyer), and a random child (Cole Hawkins). Whatever possibility existed for a fish-out-of-water scenario is firmly quashed, as Leopold instantly comprehends all aspects of modern life and is good at everything; his acting skills land him a juicy role in Kate’s latest ad for non-fat margarine, and the two quickly fall for each other.

You may be asking how a Victorian man can be better at modern life than modern man. The movie’s answer is simple: much like the Na’vi in Avatar, Victorian man is just better than us. Victorian man is a straight shooter. He can act. He can play piano. He can sweet-talk. He understands the lost arts of correspondence and flower arranging. He’ll chase down thieves who mug you in the middle of the day on Central Park East, and he’ll do it on a white horse! He can even cook (this especially bothered me; I’m pretty sure most Victorian aristocrats never set foot in a kitchen in their lives). And most importantly, he respects your boundaries, and values steady courtship. I take no issue whatsoever with these qualities, but the film’s insistent portrayal of them as both unique to and universal within the 19th century is jarring and uncomfortable.

The treatment of 2001 is no better. Modern man, you see, is either boorish like Kate’s boss (Bradley Whitford), wimpy like her brother, or unaccountably unworthy of respect like poor Stuart. Kate, explicitly a stand-in for the female audience, is a stereotypical storybook romantic who loves cuddling and hates sex, and only wears pants because she is unfulfilled– a running theme, believe it or not. Kate & Leopold’s sexual politics constantly feel as if they should be insulting to men and women alike, but are so alien as to resist outright offense. Watching it is like watching the rituals of an unfamiliar tribal culture, except the chief keeps insisting that the culture is your own.

Except for its bizarre invocation of “science” to explain an overtly magical realist plot, Kate & Leopold reminded me of two Woody Allen films with similar premises, The Purple Rose of Cairo and Midnight in Paris. But whereas those movies reject the fantasy and falsehood of a more perfect life, embracing the here and now for better or worse (and, you know, are funny), Kate & Leopold fully indulges Victorian romance. Instead of learning a lesson or having any semblance of an arc, Kate follows Leopold back to 1876. With the rift in time closing, she forever abandons her family and friends to lead a life without voting rights or antibiotics. But at least she has her Duke, who she met a week ago, and who frankly could’ve done way better.

Signs This Was Made in 2001

Kate is introduced breaking into Stuart’s apartment so she can look for her Palm Pilot. She wears Morpheus sunglasses and leather blouses, and her hair is tortuously straightened and cut to resemble straw. Leopold tries on yellow-tinted sunglasses. Mike Piazza gets namedropped.

Additional Notes

- “Leopold, Duke of Albany” was a really weird name choice for Jackman’s character. There was a real Leopold, Duke of Albany, but he was the youngest son of Queen Victoria, not a random member of the peerage. He was 23 years old in 1876, died of hemophilia at age 30, and had fuck-all to do with the invention of the elevator.

- A young Viola Davis is briefly in this movie, as a cop who orders Leopold to pick up some shit left by Stuart’s dog. Leopold takes offense at thee municipal ordinance requiring this course of action. It makes sense in context. Sort of.

How Did It Do?

Kate & Leopold grossed $76 million against a $48 million budget, likely failing to recoup its marketing. It received a 50% rating on RottenTomatoes; reviews at the time were curiously lacking in depth, so if you want to see another take on it, check out Lindsay Ellis’ tongue-in-cheek retrospective on it.

Although I can’t find any evidence that Meg Ryan financed the film, or took part in crafting the story, Kate & Leopold has every hallmark of a vanity project. At forty, the one-time standard-bearer of romantic comedy is several years older than the rest of the main cast, and seems to believe that her new, notorious upper lip injection will enable her to blend in with the MTV generation, but she’s hopelessly out of place. The script, co-written by Steven Rogers and director James Mangold, is one of the craziest and stupidest of this project, yet I end up simply feeling sad for everyone involved, particularly Ryan, who never starred in a major studio picture again.

Next Time: Black Hawk Down

|

|

|

|

Post by Hachiman on Dec 27, 2016 19:27:06 GMT -5

I just want to say thank you for writing these all up. The fall of 2001 was the start of my last year in high school and with two friends working at movie theaters, I spent a lot of time at the movies and I remember most of these movies and even the promotions from the ones I haven't seen very vividly. 9/11 obviously had a gigantic impact on pop culture, but I don't think I have really come across too many retrospectives comparing film from before and after the event. I noticed sometime in late 2002, once all the pre-9/11 movies had been burned off, that movies seemed to be somehow different. You couldn't have a comedy without someone having a personal crisis, the villains and goons in action movies were no longer just punching bags but had to represent something else as well, and the rom-coms seemed to double-down on the unrealistic worlds their characters lived in. Everything either had to mean something or had to be completely devoid of any real stakes. When I look back on these movies, most of them seem pretty light to me in the stories they were trying to tell. I guess I just miss seeing the occasional light movie.

|

|

|

|

Post by Return of the Thin Olive Duke on Dec 27, 2016 20:11:19 GMT -5

Everything either had to mean something or had to be completely devoid of any real stakes. My epilogue says almost exactly that. And how incredibly sweet of you to say all that! |

|

|

|

Post by Desert Dweller on Dec 27, 2016 21:04:28 GMT -5

Yes! It was Kate & Leopold that I once saw on tv. Well, I saw a scene from it. I remembered Breckin Meyer climbing through a window to talk to Hugh Jackman's character. That was the only thing I knew about the movie, other than the time travel. "Is that one with the time traveling Hugh Jackman and people who climb through windows?"

I enjoyed the Lindsay Ellis review, thanks. Although, damn, she made me sad that "Wolverine" sucked so badly. Liev Schreiber and Hugh Jackman work well together and clearly deserve better movies than these two.

|

|

|

|

Post by Powerthirteen on Dec 28, 2016 7:36:45 GMT -5

I'm not gonna lie, reading that summary (Kristen Schaal + High Jackman + silly shanghai knights-esque elevator plot element) makes me want this movie to have been good so badly.

|

|

|

|

Post by MarkInTexas on Dec 28, 2016 9:41:43 GMT -5

Leopold, you see, is the inventor of the elevator, an achievement stolen from him by his treacherous valet Otis (bangs head against history textbook), and with Leopold in the present, the world’s elevators have vanished, sending Stuart down an empty shaft, breaking his leg, and landing him in a hospital where he’s apparently not allowed to make phone calls.

So, when Leopold arrives in 2001, all elevators are blinked out of existence, yet buildings were still built with elevator shafts, and skyscrapers were still built with dozens of stories, even though the only way to reach the top floors was to climb dozens of flights of stairs? |

|

|

|

Post by Return of the Thin Olive Duke on Dec 28, 2016 14:26:05 GMT -5

Black Hawk Down

Dir. Ridley Scott

Premiered December 28, 2001

In January 2002, on what might have been Martin Luther King Day, my father took me to see a movie at the Pacific Theaters Hastings Ranch for what turned out to be the third-to-last time. Pasadena, a venerable and cultured city of 200,000 people, had been without an adequately sized movie theater for decades, which meant that every weekend, huge crowds would drive to a vast complex of factories and strip malls on the east end of town, and pack into the main theater at the Hastings to watch the latest event film on a screen with a dark stain in the middle. That summer, though, a new, much bigger theater with newfangled stadium seating opened right Downtown, and I never went to the Hastings again. Nobody did. It closed down a few years later. And while I don’t miss it, I still cherish memories like this.

Black Hawk Down was the first R-rated movie I ever saw in theaters. It was also the only movie my father ever took me to. He had been disappointed by Saving Private Ryan three years before and was very excited that Black Hawk Down was a true story and had an age-appropriate cast. I hated him even then, but he was certainly on to something. Behind Enemy Lines aspired to be “a new kind of war movie.” Black Hawk Down, it turned out, was the new kind of war movie.

Black Hawk Down is an unusually faithful depiction of the brutal yet little-publicized Battle of Mogadishu between American forces and the Somali militia of Mohammed Farrah Aidid, the culmination of an ill-defined UN peacekeeping mission intended to relieve famine after the fall of Communism and outbreak of civil war in Somalia (these exact circumstances are not fully explained in the film; I chose to include a broader assessment here for clarity of discussion). Leading the operation are the elite US Army Rangers and their rivals, the officially secret Delta Force. Most of the American troops don’t understand why they are there, and what should be a regular arrest mission turns erupts into a huge night-long battle when two transport helicopters are shot down over the center of Mogadishu, and the men are trapped in the City without adequate fire support, GPS, night vision, or even body armor or water.

A true ensemble piece, the movie wanders freely between points of view, but mostly follows six characters:

- Staff Sergeant Matt Eversmann (Josh Hartnett), an idealistic Ranger who is given command of his very own chalk (read: squad) when his CO (Ioan Gruffudd) is diagnosed with epilepsy.

- Specialist John Grimes (Ewan McGregor), a veteran combat clerk who is finally put on the front lines after a fellow ranger (Matthew Marsden) breaks his arm.

- Sergeant First Class Norm Hooten (Eric Bana), the cynical, hypercompetent, Somali-speaking Delta NCO who plays Han Solo to Eversmann’s Luke Skywalker.

- Captain Mike Steele (Jason Isaacs), a Ranger company commander whose concern for discipline is matched only by his fear of the comparitively wild Delta soldiers– until he gets pinned down on the wrong side of town with countless wounded men.

- Lieutenant Colonel Danny McKnight (Tom Sizemore), the Ranger commander whose job mostly consists of driving around the city looking for Captain Steele, hobbled by fatally bad directions from the surveillance pilots above.

- Major General William Garrison (Sam Shepard), who’s constantly trying to figure out what is going on.

As a kid, I loved Black Hawk Down. I devoured Bowden’s book and sought whatever information I could find about the battle soon after. But after a subsequent decade and a half of mindless Valor Porn, I feared that this film may have been no better (especially after seeing the awful theatrical trailer). I was wrong. Somehow as a young man, lost in the details of geography and tactics, I failed to appreciate the uncompromising brutality of the film as a whole, from the mummifying corpses of starved Somalis in the first shot to the anonymous airborne coffins of Americans in the last, and much worse in between. Friend and foe die horribly undignified deaths, often by rocket. COs comfort the mortally wounded with false promises of recovery. Aidid’s militiamen parade unrecovered, naked American bodies. Survivors carry on even as they go blind or deaf. This is not a pro-war movie. Merely a story that deserves to be told.

The largest criticism of Black Hawk Down has been its use of the “faceless enemy,” a problem I believe is universal to war films, and which is only really the object of concern when said enemy is non-white. In response to those complaints, I have two responses. First, the film actually goes to great lengths within the constraints of its format to give some impression of the situation in Somalia; delivering a prologue concerning the humanitarian crisis and offering opinions from a handful of Somali fighters, as well as showing how the horrors of war affect them (in fairness, I got this from a college film class on Unthinking Eurocentrism that mostly consisted of both professor and text calling racism on movies they very blatantly had never seen). Second, the mystery of the enemy is thematically very important to the film– none of the Americans in the film quite know why they’re there. Eversmann is sympathetic to the plight of the Somalis, but his understanding of the crisis is shallow. General Garrison, arguably the most intelligent character, has his heart in the right place, but realizes that even he has no idea; and in a sudden realization of his own befuddlement, he gives the film its most famous and oft-quoted line: “we just lost the initiative.”

In Mark Bowden’s book Black Hawk Down, which served as the basis for the film, Bowden stresses early on that the reason for the peacekeeping mission had less to do with famine relief than African regional politics, with the Egyptian UN Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali playing favorites in the Somali Civil War. Scott and screenwriter Ken Nolan take a more clever, cinematic route: what appears to be a clear-cut humanitarian mission executed by America’s finest becomes an inscrutable disaster, wherein even the best-equipped and best-trained men in the world can get hopelessly lost.

It is fitting that the first great war film of post-9/11 America was a story about people who think they know everything, only to realize, in a few bloody hours, that they don’t know anything.

Signs This Was Made in 2001

The most obvious sign comes at the very beginning, when a subtitle reads “Somalia, East Africa.” Of course, the African nation’s later reputation for piracy would make it a household name.

Despite being made only eight years after the events portrayed, Black Hawk Down is remarkably faithful to the period, a feature that is most notable when you see the clothes and bulky cell phones favored by the Somalis. Only the most cursory of anachronisms reveal the movie’s vintage: the appearance of a pair of Oakley Juliet sunglasses and a paperback edition of John Grisham’s The Client.

Additional Notes

- In light of some other films of that era which had been based on real events, Black Hawk Down is surprisingly true to what happened. The biggest outright change was Scott’s decision to label each Ranger’s helmet with their name, which I personally find genius. One of the biggest problems with war movies, assuming the filmmakers are trying to represent real people, is that it’s very hard to tell characters apart when they are in uniform, especially when they share similar physical attributes and overlapping character traits– compare to Band of Brothers, which also aired in the fall of 2001, wherein the format of television provides more time to get to know the men. By labeling the helmets, Scott not only enables the audience to identify the characters immediately, but also subconsciously highlights the subtle differences between them. Bravo!

- Because war movies have such large, young casts, it’s easy to spot faces that would later become famous. Here, aside from those already mentioned, we find Tom Hardy, Ewen Bremner, Ioan Gruffudd, Nikolaj Coster-Waldau, Jeremy Piven, Ty Burrell, and Zeljko Ivanek. Hardy, who also had a one-off role in that fall’s Band of Brothers, is a particular standout as Specialist Twombly.

- Black Hawk Down’s eclectic score is also notable, and certainly influenced later war-themed and African-set films. At times it sounds suspiciously like an orchestral version of Vangelis’ score from Ridley Scott’s earlier film Blade Runner.

- Depicted with gut-wrenching horror in the film, the folly of using unarmored humvees in urban combat should have been heeded in anticipation of the Iraq War. The consequences, as we all discovered, went far beyond even the carnage displayed here.

How Did It Do?

Black Hawk Down defined the war movie for the 21st century.

Among 2001 releases, it is second only to The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring in its influence, establishing new standards for cinematic depictions of battle in terms of direction, cinematography, editing, sound design, and music. This cannot be understated. It grossed $173 million against a $92 million budget, likely failing to recoup its marketing expenses through the box office, but doing very well through DVD sales. The film was critically applauded, though not universally, earning a 76% fresh rating on RottenTomatoes. It was nominated for four Academy Awards, including Best Director for Ridley Scott, and won an Oscar each for editing and sound mixing.

None of that would’ve happened if not for the September 11 Attacks.

Whatever Sony Pictures may have thought, Black Hawk Down was a critical and commercial underdog. It largely eschewed Hollywood archetypes or even a discernible main character in favor of a broader, more realistic depiction of how they interact as a group. And while it’s not quite an epic tragedy, it’s not far off. It drew attention to the internal politics and rivalries of a US military that had grown unfamiliar and irrelevant. It was set outside the typical European and Asian milieu of most American war films. Most strikingly, it was based on an obscure battle that didn’t even make front-page news when it happened.

The day after the Battle of Mogadishu, the only news of the battle in US newspapers was that an American pilot had been taken prisoner. Beyond that, public consciousness of the battle was limited to a few inexplicable passing images of American bodies being dragged naked through unfamiliar streets. Only after finishing most of this review did I remember that the US military had purposely withheld the full extent of the battle from the press, involving as it did an officially secret unit.

Beyond the veil of military secrecy, it’s worth examining why the battle failed to make an impact in its own time. Despite the end of the Cold War, the period from 1991 to 2001 was not without conflict or bloodshed. The breakup of Yugoslavia, Rwandan Genocide, and Great War of Africa all occurred during this period, but without any overarching global conflict, these events seemed less important in the public mind. Hell, Al Qaeda attacked the United States repeatedly throughout the 1990s, yet Republicans laughed off the Clinton White House’s anti-terrorism efforts as a quixotic wild goose chase, which is the one of the reasons 9/11 happened, and domestic terrorism remained the foremost threat in the public mind (at least after killer bees). The Somali episode, despite being the bloodiest day in American military history since the Vietnam War, was even more buried than most conflicts of that era; hence the film’s need to explain that any of this happened at all.

Ever since 2001, it is unthinkable that such an incident could go unnoticed. Terrorism and war are sadly familiar, by experience and by proxy, to the western world, and though the United States and its allies have been technically been at peace for nearly two years, the impact of major battles in countries like Syria, Iraq, and Libya continue to be felt in our lives. That’s why Black Hawk Down was a big deal. And it is for this reason that I wish this could be the last film I talk about for this project.

Unfortunately, alphabetical order demands otherwise.

Next Time: I Am Sam

|

|

|

|

Post by ganews on Dec 28, 2016 15:18:14 GMT -5

Upvoted for use of "Valor Porn". I saw this in the theater over Christmas with male family members. Although I remember details about all sorts of movies I have seen, I remember almost nothing from this, except someone gets a thumb blown 90% off, and the movie has William Fichtner. I ought to watch it again just for that great cast list.

|

|

|

|

Post by Return of the Thin Olive Duke on Dec 29, 2016 11:32:30 GMT -5

I Am Sam

Dir. Jessie Nelson

Premiered December 28, 2001

Black Hawk Down and I Am Sam were the last wide-releases of 2001, and by virtue of alphabetical order, I Am Sam is the last film of this project. For this to be the last film discussed in the context of 9/11 is annoying. Black Hawk Down had so much more to work with. Alas, I Am Sam is a film of at least some anthropological importance that bears discussing.

Sam Dawson (Sean Penn), a mentally handicapped Los Angeles man who works at Starbucks, becomes a proud father when a nameless woman staying with him gives birth to a daughter (Dakota Fanning), whom he names “Lucy” after “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds” due to his obsession with The Beatles. The mother immediately disappears, and Sam is totally clueless about the basics of raising a child, but he’s helped along the way by his “endearingly” agoraphobic neighbor (Dianne Wiest). Trouble arises when young Lucy begins to surpass her father mentally and becomes increasingly embarrassed by his developmental state.

The crux of Sam’s woes begins with one of the most bizarre sequences of events I’ve ever seen in an A-list film. In what may be the first scene set inside Los Angeles’ Grand Central Market since Blade Runner, Sam is arrested for...talking to a hooker. Yeah, he’s arrested for solicitation, but at no point did the woman in question proposition him, or vice-versa. Call me naïve, but I don’t think conversing with a prostitute has ever been illegal. The incident exists simply to get Sam into court and is never mentioned again. With the state threatening to put Lucy into foster care, Sam seeks the help of family lawyer Rita Harrison (Michelle Pfeiffer), an overworked, neurotic career woman stereotype who is shamed by her coworkers into taking Sam’s case pro bono.

If I Am Sam is remembered today for one thing, it’s that Penn, in the words of Ben Stiller’s classic Hollywood satire Tropic Thunder, “went full retard” and thus flew too close to the sun in his quest for accolades. Penn’s performance is mostly serviceable. I know Sam is supposed to be kind of obnoxious, but he’s still less obnoxious than the actor in real life. But make no mistake: the film is a disaster, thanks mostly to the script.

If I Am Sam is remembered for two things, it’s that the government spoilsports (represented here by Richard Schiff) are totally in the right. However much Rita may proclaim from the bench that Sam’s mental ability “does not affect his capacity to love” (woof), the fact remains, and the film openly demonstrates, that Sam is fundamentally unfit for raise Lucy. Sam himself seems to realize that fact, and all but the filmmakers can see it.

We know this, but I was surprised by how ugly the film is. Nearly every shot is a closeup, most of it handheld, and much of it in POV. The production design is nearly as awkward and uncomfortable as the cinematography; the narrow, circular courtroom is impractical and deeply uncinematic, and the choice to build the set like that is fairly representative of the film as a whole. It’s overloaded with product placement, attempting to do for Starbucks what Cast Away did for FedEx. Pizza Hut, IHOP, and Bob’s Big Boy are also represented, yet other trademarks are conspicuously avoided, such as Rita complaining about her son’s “Raptor Scooter” (read: Razor Scooter), or her phone’s carefully altered Nokia ringtone. The screenwriters, who produce some of the most laughable lines ever meant for consideration by the Academy, apparently can’t even spell-check, as evinced in a scene where an erudite neurotypical man twice uses the term “anthropods” when he means “arthropods.”

On every level, perhaps bar the acting, I Am Sam is justifiably remembered as the gold standard of Oscar Bait at its very worst; a cloyingly sentimental piece exploiting a supposedly “heavy” and “relevant” issue, even going so far to explore the implications of its premise before throwing it all away, with no thought for actual character, story, or filmmaking.

Signs This Was Made in 2001

- Sam is “mentally retarded.” Not “mentally challenged,” not “mentally disabled,” not (the frustratingly open to interpretation) “intellectually challenged,” but “mentally retarded,” and so referred to in a court of law. Though my mother, a schoolteacher, informs me that this is becoming the standard term once more, that doesn’t stop one particular “dramatic” speech by Michelle Pfeiffer from becoming unintentionally hilarious. (It’s in the trailer)

- I Am Sam’s soundtrack is composed entirely of Beatles covers. The contributing artists were all well-established at the time, with one notable exception: the film’s version of “I’m Only Sleeping” was the first song ever released by Australian garage band The Vines, who broke out the following summer.

Additional Notes

- Sam’s new neighborhood at the end of the film is the same one from the end of Training Day, repainted and beautified by the makers of that film in return for temporarily dressing it like a bullet-riddled slum.

- Why do buses in movies still have rhombus-shaped sliding windows? As someone who has ridden city buses in Los Angeles and elsewhere, I was continually confounded at how Sam would be shown boarding a brand new 2001 model bus only to cut to him clearly riding in a stock vehicle from the 1970s.

How Did It Do?

I’m sad to say that I Am Sam was a hit, grossing $97.8 million against a $22 million budget. Sean Penn was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor in a Lead Role but did not win. And Dakota Fanning’s career was launched, as well as that of her younger sister Elle, who played Lucy at age 2, so not a total loss. Jessie Nelson, a first-time director who had previously hit it big as screenwriter of feel-good blockbuster Stepmom, went on to produce smarmy Nancy Meyers-type films like Hope Springs and Danny Collins before directing her second film, 2015’s Love the Coopers. She is currently set to direct another feature titled The Most Wonderful Time.

The reviews for I Am Sam are some of the strangest I’ve come across for any film. The movie earned a 34% rating on RottenTomatoes, and even the bulk of the critics who liked it didn’t seem to like it, pillorying the movie as mawkish and unmotivated before recommending it on general principle. The negative reviews are virtually identical but for a small and committed subset of critics on the political Right who outright opposed the film and everything they believed it to represent.

There are many words I could use to describe I Am Sam, but “unpatriotic” never came to mind while I was watching it. Yet lots of people at the time– published, RT-approved film critics– found it the epitome of liberal PC thuggery. Maybe it’s just the fact that Sean Penn is such an overtly political actor (and he should really stop that). Maybe it’s the not-at-all thought-out “Free to be You and Me”-ness of it. And it’s telling to see the short-lived dynamic of the Bush years, in which opposition to Big Government was perceived as the province of the Left, beginning to emerge. But the way I see it, the fact that this was some critics’ immediate thought is the first sign that, in the final days of 2001, the September 11 Attacks were no longer the catalyst of fraternity and bipartisanship that they had previously been. In that sense, and that sense alone, the aftermath of 9/11 was over.

Next Time: Twelve More Movies I (Maybe) Should Have Reviewed

|

|

|

|

Post by ganews on Dec 29, 2016 12:29:45 GMT -5

Went full retard, went home empty-handed.

|

|

|

|

Post by Return of the Thin Olive Duke on Dec 30, 2016 14:59:26 GMT -5

Twelve More Movies I (Maybe) Should Have Reviewed For This Project

When I started this project, I wasn’t totally finished with my 2007 retrospective. In planning Aftermath, 2001, I was not eager to see 59 more films of mostly low quality, so I tried to avoid seeing several for technical reasons. But I realized that I was trying to gauge mass appeal, and these were movies that were in theaters at the time, so here are several films I perhaps should have included.

Joy Ride

Dir. John Dahl

Premiered October 5, 2001, alongside Max Keeble’s Big Move, Serendipity, and Training Day

Joy Ride stars Steve Zahn, Paul Walker, and The Glass House’s Leelee Sobieski. It’s basically Steven Spielberg’s TV movie Duel, but with a bigger cast and a body count– you may be unsurprised to learn the screenwriter was JJ Abrams. It didn’t make back its marketing budget, which was par for the course, but it was pretty well-received by critics and I slightly regret not having it here.

My First Mister

Dir. Christine Lahti

Premiered October 12, 2001, alongside Bandits and Corky Romano

I would have liked to see this as well. Even if critics were divided, I’m a sucker for intergenerational friendships, such as the one here between Albert Brooks and Leelee Sobieski (the last film of her month-long career as a movie star).

Mulholland Drive

Dir. David Lynch

Premiered October 12, 2001, alongside Bandits and Corky Romano

Of all the films I didn’t cover in this series, David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive is easily the least forgivable. Recobbled from a failed television pilot, the film was adored by critics and redeemed David Lynch in the eyes of many. I have yet to see it.

Waking Life

Dir. Richard Linklater

Premiered October 19, 2001, alongside From Hell, The Last Castle, and Riding in Cars with Boys

Richard Linklater’s rotoscope-animated existential docufiction was beloved by critics at the time, but seems to be more coolly received these days. I probably wouldn’t have much patience for it. I never liked when my film theory professor started droning about André Bazin.

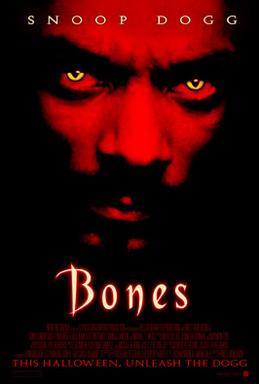

Bones

Dir. Ernest Dickerson

Premiered October 26, 2001, alongside K-PAX, On the Line, and Thir13en Ghosts

Savaged by critics and avoided by audiences, Bones is the one where Snoop Dogg is a blaxploitation zombie. Yeah.

The Man Who Wasn't There

Dir. Joel and Ethan Coen

Pemiered November 2, 2001, alongside Domestic Disturbance and Monsters, Inc.

If Mulholland Drive was the least forgivable omission in theory, this was the least forgivable in practice, as I’ve actually seen it! Starring Billy Bob Thornton as “a barber who wants to become a dry cleaner,” it’s probably the Coen Brothers’ most obscure film and among their least accessible, but I like it.

Tape

Dir. Richard Linklater

Premiered November 2, 2001, alongside Domestic Disturbance and Monsters, Inc.

Yeah, this...it’s shot on videotape, and it all takes place in one room. It sounds kinda gimmicky. Meh.

Heist

Dir. David Mamet

Premiered November 9, 2001, alongside Gosford Park, Life as a House, and Shallow Hal

I got nothing.

Monster's Ball

Dir. Marc Forster

Premiered at AFI Fest November 11, 2001

Monster’s Ball is famous for one reason and only one reason: it got Halle Berry the Oscar. This is easily the most forgivable omission from the project, as it premiered at AFI fest solely to qualify for the Oscar. I have read about it and have no interest in seeing it.

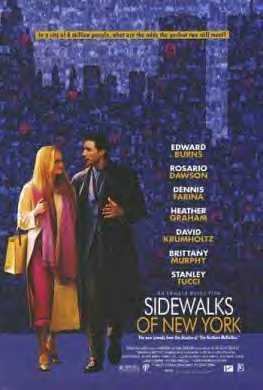

Sidewalks of New York

Dir. Edward Burns

Premiered November 21, 2001, alongside Black Knight, Out Cold, and Spy Game

So this is set in New York, and was kind of a thing, and nobody really liked the film, but everybody thought it was pleasant. Moving on.

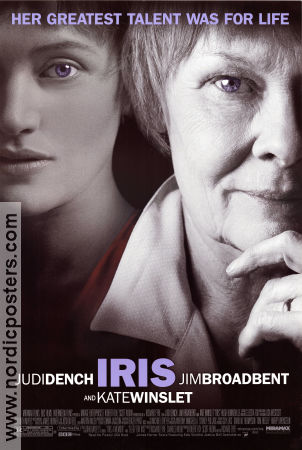

Iris

Dir. Richard Eyre

Premiered December 14, 2001, alongside Not Another Teen Movie, The Royal Tenenbaums, and Vanilla Sky

Iris is a biopic of the risqué novlist Iris Murdoch, played Love & Mercy style by both Kate Winslet and Judi Dench. Jim Broadbent won his Oscar for it, which is nice.

In the Bedroom

Dir. Todd Field

Premiered November 23, 2001

If In the Bedroom is remembered for anything today, it’s held up by cinephiles as exactly the type of “good enough” movie that enthralls Oscar voters and gets widespread mild approval from critics, but inspires no passion. In 2007, that was Things We Lost in the Fire. This year, it’s Miss Sloane (be honest). And in 2001, it was In the Bedroom. Tom Wilkinson and Sissy Spacek are married, and their son’s in love with an older woman, and Spacek’s ex husband is a creep. Tensions simmer. The end.

Next Time: What Came Next

|

|

|

|

Post by Powerthirteen on Dec 30, 2016 15:46:03 GMT -5

Several of those posters have reminded me that posters where the faces go A B C but the names go C B A make my skin crawl. It's probably some very minor form of mental illness. The Iris poster is especially painful to me. I know billing order is a contract thing but it still seems wrong.

|

|

|

|

Post by Ben Grimm on Dec 30, 2016 15:46:30 GMT -5

Heist is fun, but nothing extraordinary. I liked The Man Who Wasn't There and never understood all the flack it got. And I quite enjoyed Waking Life; it felt like Slacker (which I never enjoyed) except done properly.

|

|

|

|

Post by Superb Owl 🦉 on Dec 30, 2016 15:49:18 GMT -5

Pointless Anecdote: All through high school my group of friends remembered seeing the preview for Joyride and intended to rent it, but none of us could remember the name of the movie.

|

|

|

|

Post by Desert Dweller on Dec 30, 2016 19:03:22 GMT -5

No wonder I didn't recognize any of the movies in this thread. Monty was saving all the films I did know for the "honorable mention" list! Aha!

Mulholland Dr - I like it.

Waking Life - I like it.

The Man Who Wasn't There - It's okay

Heist - It's fun

Monster's Ball - Ugh, no.

Iris - Pretty good. Love Dench and Broadbent in it

In the Bedroom - The movie is okay, but I LOVE Tom Wilkinson and Sissy Spacek's performances.

|

|

|

|

Post by firstbasemanwho on Dec 31, 2016 0:57:05 GMT -5

This was a fun read. The ones I've seen all the way through are Zoolander, Royal Tenenbaums, Monsters Inc., Harry Potter, and LOTR. A few others I've seen bits and pieces of there (My mom loves Serendipity, natch.)

Nothing more to add except I remember those ads for Corky Romano. Oh, I remember. I want to punch that poster so bad.

|

|

|

|

Post by Return of the Thin Olive Duke on Dec 31, 2016 14:55:57 GMT -5

What Came Next

The aftermath of 9/11 did not end on New Years’ Day, 2002. The airline industry was in free-fall. The economy went into a recession. An entirely new national security apparatus was erected. Airport security got serious. The longest war in American history began. A year and a half later, we began another war, pretty much just for the hell of it. We lost some of our freedom. We lost a way of life. Black clothing became standard. A generation held its breath, and a period of mourning began which lasted years.

Hollywood, meanwhile, was saved. Saved from empty schmaltz and hollow destruction. At least mostly. We may still complain whenever Rob Reiner puts out another turkey, but at least it isn’t the norm anymore. In 2016, people have complained about a “bad” year for movies, mostly focusing on huge would-be tentpole blockbusters (and we’ll get back to that), but if this was a bad year for movies overall, we are fucking spoiled.

The fall of 2001 proved that, in time of national tragedy and distress, people wanted either escape or validation. The vast majority of films released in 2001 provided neither. The few that did were welcomed, and set the path forward to today.

Writing of her father’s intention to have his ashes shot out of a cannon upon his death, author Sarah Vowell said that when that time comes, she will not cover her ears, because “I want it to hurt.” And so, in the aftermath of 9/11, critics and audiences largely avoided the plucking of heartstrings in favor of crooked cops, schizophrenics, serial killers, dark lords, and pyrrhic victories. It turned out that “feel-good” movies were really movies for people who already felt good.

At the same time, we sought laughter and imagination. In the first Oscar ceremony after the attacks, Errol Morris presented a short documentary about why people love movies, in which once-and-future California Governor Jerry Brown proclaimed “movies are an escape.” “Just an escape?” the director asked. Brown raised his eyebrows and replied “Well, what’s wrong with that? That’s quite a lot!” And so we rejoiced in mugging male models, friendly childhood monsters, wizards, con men, boy geniuses, and hobbits.

It would be the better part of a year before Hollywood could adjust to the new normal, but the fall of 2001 gave studios time to make some changes. The Twin Towers were removed from the second act montage in Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man. The climax of Men in Black II, which had been set at the World Trade Center, was re-shot at the Statue of Liberty. Release of the Arnold Schwarzenegger vehicle Collateral Damage was postponed to February 2002 due to its terrorism content, which was then downplayed in advertisements. More drastically, The Bourne Identity, originally expected to flop in September 2001, was postponed by nine months, with a re-written and re-shot ending, and was a hit.

For the most part, this new normal fed the public’s new emotional desires, resulting in movies that, if not better, were at least more interesting. Far more notable, though, was the impact made by The Lord of the Rings franchise that stepped right into the vacuum 9/11 created. Obviously the introduction of the Harry Potter films had something to do with it, and the blurring of the comparative stature between film and television, each becoming more similar to the other, but it was LOTR that set the new standards for big-budget Hollywood entertainment. Today, we live in a world of cinematic “universes:” Star Wars, Marvel, (ugh) DC, (super ugh) Hasbro. That may not last. You may be surprised to learn that average film budgets actually went down after 9/11, mainly because of the collapse of star power as an incentive to see movies, and profits soared because of it. Today, massive blockbusters are becoming prohibitively expensive, with every major studio banking on one or two movies to make at least a billion dollars just to break even– and last summer, only Disney succeeded. Meanwhile, microbudget is increasingly popular among the mainstream, and studios like A24 have emerged to create genuine low-budget blockbusters, so change may be in the air. But only time will tell.

Next Time: 1977 |

|