Post by Return of the Thin Olive Duke on Sept 19, 2016 10:02:13 GMT -5

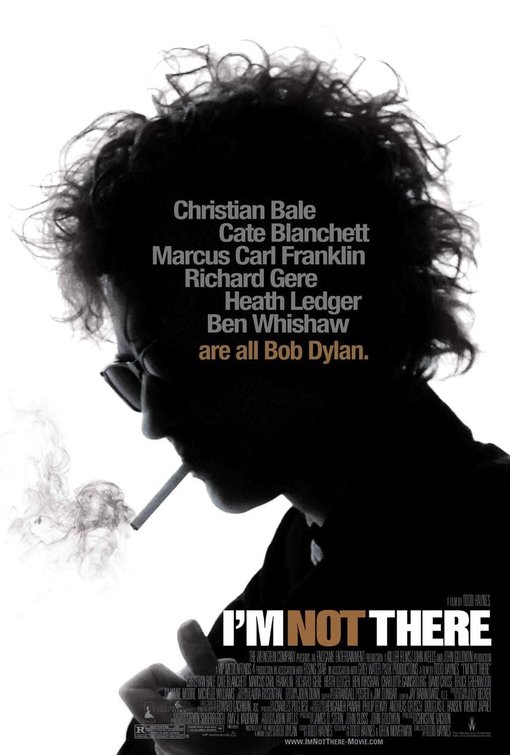

I'm Not There

Dir. Todd Haynes

Premiered November 21, 2007

Right before the advent of Netflix, my mom went through this phase where she would go to Blockbuster and rent the weirdest, most niche DVDs she could find; and one of them was called Palindromes. I’ll spare you the details; look it up if you’re curious, it’s one of those movies that make you wonder in retrospect if you didn’t just imagine it while suffering from the flu; the relevant point is the main character in that movie is played by many different actors. So when I heard about a new film about Bob Dylan that did the same thing, I assumed that it was being helmed by the director of Palindromes, Todd Solondz, and thought nothing more of it until college.

Some five or six years later, I was taking a class at SF State that might as well have been called Music Theory Masturbation for People Who Couldn’t Get Real Classes Because of Austerity Cuts AND Massive Embezzlement,* and one of the movies we saw was I’m Not There. I was sick the first day of the showing, so I only saw what I thought was the second half, and it was weird. Really weird. But not necessarily bad. It certainly left an impression. And of course, I found out the director was a different Todd, Todd Haynes, whose film Velvet Goldmine I saw years later still in film school and absolutely loved.

Making Velvet Goldmine, Haynes was unable to get the rights to David Bowie’s life story (legal difficulties with popular musicians is something of a tradition for the filmmaker), and so told a fictionalized history of ‘70s glam rock through symbolic figures. I’m Not There had no such legal trouble with its subject, Bob Dylan, and still took the same route– going even further. The film is a rapid-fire anthology of stories about characters embodying different aspects or periods of Dylan’s life, and even individually they are out of order, and seemingly only half complete.

Even if the vignettes are not chronological, they do follow a sort of chronological order, beginning and ending in roughly the same order, each with a distinct cinematic and musical style:

Like any anthology film, certain of these stories and characters will be stronger than others. Back in 2007, most were drawn to Jude Quinn, who is the most readily familiar incarnation of Mr. Dylan as popular culture has chosen to remember him, and it got Cate Blanchett and Oscar nomination. Minnie loved Robbie Clark, despite the character’s tenuous connection to Dylan’s body of work, but that’s mostly a testament to Ledger, whose untimely death cost the world a lifetime of great performances. In what I suspect may be an unpopular opinion, I was personally enthralled with Billy the Kid, not least because I’m actually most familiar with Bob Dylan’s quasi-western 1970s output due to my father’s incessant playing of records like Blood on the Tracks and his work with The Band.

Roger Ebert in his review of this film complained that the movie doesn’t give any further insight into Dylan as a person. I think it does– it’s just deeply cynical. Or perhaps Zen. I’m Not There tells the story of a creative genius who can only express that genius through various personas, Peter Sellers-like.

Yet the director doesn’t judge. With Velvet Goldmine, Haynes seemed to view the abandonment of glam rock as a betrayal of a way of life and thinking in favor of a hollow corporate musical environment. Nearly a decade later, a firmly middle-aged Haynes openly mocks such reactionary fandom, such as that which rejected Dylan’s rock stylings as a betrayal of their values. I’m Not There is all about mortality, hence the involvement of Rimbaud. Yet the film’s fatalism is a hopeful one, one which gives nostalgia its due but recognizes the need and indeed the endless possibilities of change.

Sign This Was Made in 2007

The narrator calls Vietnam “the longest war in television history.” No longer.

Additional Notes

Also in Theaters

In anticipation of the Thanksgiving holiday, Enchanted and I’m Not There debuted Wednesday, November 21. The same weekend saw the release of August Rush, Hitman, The Mist, and This Christmas, the latter of which I will never forgive for producing Chris Brown’s freakishly durable cover of the Motown carol of the same name (yes, I've worked in holiday retail).

Next Time: The Savages

Dir. Todd Haynes

Premiered November 21, 2007

Right before the advent of Netflix, my mom went through this phase where she would go to Blockbuster and rent the weirdest, most niche DVDs she could find; and one of them was called Palindromes. I’ll spare you the details; look it up if you’re curious, it’s one of those movies that make you wonder in retrospect if you didn’t just imagine it while suffering from the flu; the relevant point is the main character in that movie is played by many different actors. So when I heard about a new film about Bob Dylan that did the same thing, I assumed that it was being helmed by the director of Palindromes, Todd Solondz, and thought nothing more of it until college.

Some five or six years later, I was taking a class at SF State that might as well have been called Music Theory Masturbation for People Who Couldn’t Get Real Classes Because of Austerity Cuts AND Massive Embezzlement,* and one of the movies we saw was I’m Not There. I was sick the first day of the showing, so I only saw what I thought was the second half, and it was weird. Really weird. But not necessarily bad. It certainly left an impression. And of course, I found out the director was a different Todd, Todd Haynes, whose film Velvet Goldmine I saw years later still in film school and absolutely loved.

Making Velvet Goldmine, Haynes was unable to get the rights to David Bowie’s life story (legal difficulties with popular musicians is something of a tradition for the filmmaker), and so told a fictionalized history of ‘70s glam rock through symbolic figures. I’m Not There had no such legal trouble with its subject, Bob Dylan, and still took the same route– going even further. The film is a rapid-fire anthology of stories about characters embodying different aspects or periods of Dylan’s life, and even individually they are out of order, and seemingly only half complete.

Even if the vignettes are not chronological, they do follow a sort of chronological order, beginning and ending in roughly the same order, each with a distinct cinematic and musical style:

- 19th Century French poet Arthur Rimbaud (Ben Whishaw), being questioned about the nature of fatalism in a Cold-War era interrogation room that may or may not be purgatory. Rimbaud, as well as the film’s narrator (Kris Kristofferson) serve as something of a greek chorus to the rest of the film.

- An 11-year-old black troubadour calling himself “Woody Guthrie” (Marcus Carl Franklin) who rides the rails and sings for the union cause despite living in 1959, until one of his many hosts (Kim Roberts) tells him to sing about his own times. The character is a reference to Dylan’s early fixation with the real Woody Guthrie, as well as his tendency to tell tall tales about his origins– though his portrayal as a poor black child may owe more to Steve Martin.

- Jack Rollins (Christian Bale), a protest singer who abandons his craft after publicly comparing himself to Lee Harvey Oswald, and years later becomes an evangelical pastor and gospel musician. His story is told through the guise of a PBS-style documentary interviewing his friends and colleagues, such as Alice Fabian (Julianne Moore), based on Dylan’s real-life friend and rival Joan Baez.

- Robbie Clark (Heath Ledger), a young actor who plays Rollins in a 1965 film, through which he meets and marries French painter Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg) and becomes an eventual darling of the New Hollywood. The rise and fall of their relationship coincides with and parallels the American war in Vietnam.

- Jude Quinn (Cate Blanchett) most closely parallel’s Dylan’s public image, especially as depicted in the 1967 documentary Don’t Look Back. Quinn betrays the folk scene by adopting the electric guitar, futzes around England and America alike, goes to groovy parties, feuds with standoffish British journalist Keenan Jones (Bruce Greenwood), and generally resents his supposed position as standard-bearer of America’s youth.

- Billy the Kid (Richard Gere), having escaped his supposed execution at the hands of lawman Pat Garrett (also Bruce Greenwood) and settled into an anonymous existence in the small town of Riddle, Missouri. Around the time of World War I, Riddle is set to be destroyed by a newfangled public highway, and Garrett is behind it. This segment was inspired by Dylan’s soundtrack for Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid.

Like any anthology film, certain of these stories and characters will be stronger than others. Back in 2007, most were drawn to Jude Quinn, who is the most readily familiar incarnation of Mr. Dylan as popular culture has chosen to remember him, and it got Cate Blanchett and Oscar nomination. Minnie loved Robbie Clark, despite the character’s tenuous connection to Dylan’s body of work, but that’s mostly a testament to Ledger, whose untimely death cost the world a lifetime of great performances. In what I suspect may be an unpopular opinion, I was personally enthralled with Billy the Kid, not least because I’m actually most familiar with Bob Dylan’s quasi-western 1970s output due to my father’s incessant playing of records like Blood on the Tracks and his work with The Band.

Roger Ebert in his review of this film complained that the movie doesn’t give any further insight into Dylan as a person. I think it does– it’s just deeply cynical. Or perhaps Zen. I’m Not There tells the story of a creative genius who can only express that genius through various personas, Peter Sellers-like.

Yet the director doesn’t judge. With Velvet Goldmine, Haynes seemed to view the abandonment of glam rock as a betrayal of a way of life and thinking in favor of a hollow corporate musical environment. Nearly a decade later, a firmly middle-aged Haynes openly mocks such reactionary fandom, such as that which rejected Dylan’s rock stylings as a betrayal of their values. I’m Not There is all about mortality, hence the involvement of Rimbaud. Yet the film’s fatalism is a hopeful one, one which gives nostalgia its due but recognizes the need and indeed the endless possibilities of change.

Sign This Was Made in 2007

The narrator calls Vietnam “the longest war in television history.” No longer.

Additional Notes

- *Another class I took that semester was Origins and Early History of Rock, which was way above my grade level, but was still a really cool way to spend a Friday morning.

- One of the strangest things in the film is actually true. Black Panther party heads Huey Newton and Bobby Seale did indeed listen obsessively to Dylan’s “Ballad of a Thin Man” in the belief that it was about them. Somehow.

Also in Theaters

In anticipation of the Thanksgiving holiday, Enchanted and I’m Not There debuted Wednesday, November 21. The same weekend saw the release of August Rush, Hitman, The Mist, and This Christmas, the latter of which I will never forgive for producing Chris Brown’s freakishly durable cover of the Motown carol of the same name (yes, I've worked in holiday retail).

Next Time: The Savages