Season 5 Ep 9 / 10 "Thirty Days" / "Counterpoint"

Dec 10, 2015 14:36:22 GMT -5

Jean-Luc Lemur and bumsrussiawithglove like this

Post by Prole Hole on Dec 10, 2015 14:36:22 GMT -5

Season Five, Episode 9 - "Thirty Days"

Voyager To The Bottom Of The Sea

Genre tropes in fiction, as "Darkling" demonstrated, need more than just the existence of them within a specific episode to function or make their use worthwhile. Just empty repetition is boring - the basics of the genre are visible but if you don't do something interesting with them then it just looks like you're being lazy, that an episode has nothing else going for it so here, stick in these familiar bits, people will recognise it, and we can move on to something else. This is what I've referred to in the past as genre collision - taking the specifics of a certain type of story, in this case 19th century sea-faring adventure fiction, and colliding it with the world of Star Trek to see what happens, as "Thirty Days" does. The results, which are delightful, more than justify the exercise of genre collision here, and actually have something useful to say and add to our ongoing characters and stories.

Saying that, though, there's one thing that pretty much needs to be put aside at the beginning, and that is of course scientific plausibility. The episode does slightly gets away with this, because what we get here is, not for the first time this season, a narrative which is slightly left-of-centre, which is to say this is not being delivered by an omnipresent narrator as most episodes are, but instead events are being related to us via the perspectives of a single character. This means that what we get told about here isn't necessarily the literal truth of what happens but instead what Tom recalls, remembers, or otherwise makes up. He's trying to justify his behaviour to his father, but of course it's in the nature of self-justification to put oneself in the best light, and that includes the circumstances one finds oneself in. So while the ocean in space is an immediately striking image on its own, and we have no reason to doubt its veracity, later when Tom tries to stop a breach in the hull several hundred kilometres down by just putting his hands over the leak it looks silly (he, and indeed the Delta Flyer, would just implode). But this is just his way of telling the story, so the fact that it’s not a literal representation of the facts means the episode doesn’t need to commit to a sense of “real” reality in the way a standard episode would. While this helps paper over any number of implausible events, there's more than enough of Star Trek's own reality to conclude what we're being told is, if not 100% of the truth, at least close enough to make what we see here seem likely, so while Tom may be an unreliable narrator, he's not too unreliable. And though we hear specific mention made of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea, and though it's possible for the Delta Flyer to double as a Nautilus stand-in, events here actually have as much in common with that other great titan of 19th century sailing fiction, Treasure Island. The parallels are many, with the main part of the story here being told in "first person" (which is to say, by Tom) just as in Treasure Island; the central character of the narrative is also the person who is actually narrating the story; and you could even go so far as to suggest that the reactors under the ocean qualify as "buried treasure" (certainly their value to the Moneans is without parallel, and it is vague X shaped, as in "marks the spot"). And, if you really want to push it, Treasure Island is also a coming-of-age story, just as Tom "comes of age" by finding a cause to fight for that he genuinely believe in, rather than one he just drifted into looking for a fight, as with the Maquis (and the importance of it being B'Elanna who points this out to him shouldn't be missed either). Which is not to say that there aren't any parallels with Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea, because there are, most obviously with it's "fiction predicts the future" conceit; the famous giant cuttlefish battle being suggested by the massive "electric eel" the Flyer runs into on its first dive into the deep; and the fact that Nemo himself is often depicted as standing up for those who cannot defend themselves (which in this context is both the ocean itself and the Moneans who would otherwise suffer because of administrative inaction). The point of drawing all these parallels is to show just how steeped in the genre of 19th century fiction this is, while still functioning very much as a Star Trek story, because it's able to successfully update the iconography of the past to make it usefully function in the future.

Of course there's also the very 20th century aspect to the story as well, which is that it functions as a not-exactly-subtle environmental parable as well. The Mineans are exploiting the ocean for their own good which is bringing around the collapse of the very ecosystem they are dependant on for their survival. Not what you would call subtext, is it? Yet it's this inclusion that really makes the episode work as more than just a hollow genre pastiche because here we find one of the two reasons for the episode to exist. By functioning as an environment parable this isn't just fun and games that could just as easily have been done on the holodeck, it gives some actual stakes to the story, and by doing so gives a purpose to the borrowed iconography. Exploitation of the oceans was a big environmental issue in the 1990s, between oil spills (the most well known of which was the Exxon Valdez oil spill, which actually happened in 1989), whaling, fish being caught to the point of stocks collapsing, plastics pollution... doing a story specifically about an oceanic environment feels very 1990s, but in a representative way rather than doing a broader global warming or ozone layer-type story. So again we see the fit of the iconography and the story - a very 90's concern filtered through both the 19th and 24th centuries, while at the same time delivering an entertaining, engaging episode. And of course the use of Captain Proton here is also significant, this time taking early 20th century imagery and using that as a starting point for Tom's motivation to get involved - Tom's heartfelt, "no Captain Proton to the rescue this time" is the jumping off point for B'Elanna to push him just that little bit further, and of course Captain Proton is exactly the kind of adventure serial (along with Westerns) that Star Trek draws its roots from.

The final purpose of the episode is to give Tom some character development, and push him just that little bit further outside his comfort zone. Since his settling down with B'Elanna he's been a more stable character, still a little roguish but obviously better off for being in the relationship. Here we get to see him stretching out in more rebellious directions, again very much in line with the hero-of-his-own-story that both Jim Hawkins and Captain Nemo represent. We haven't had any specific mention of his interest in 19th century fiction before but this still feels perfectly in line with a character who tinkers with old cars on the holodeck and enjoys Captain Proton in his spare time. Certainly his interest in historical fiction feels character consistent, as does his expanded sense of responsibility. For all his joking with whatever character needs a line to be included in the episode while he's in solitary, it's clear from the actions that what we see here that this is a deliberate choice, and one he is willing to accept the consequences of. This is very far from the rash, impulsive character of earlier in the show and instead we see someone who's learned the lessons Janeway has been trying to teach - indeed, learned them all too well, so that his sense of responsibility overwhelms his sense of duty or his ability to follow orders. Yet this never pushes him into territory where you feel like the character is acting like an idiot for not just doing what he's damned well told, and this is, again not for the first time, because both his arguments and Janeway's arguments are correct. He's right that the Moneans clearly aren't going to do a thing to try and resolve the situation, and Janeway is right that it's not up to them to hector every society them come across into doing what they think (the Monean minister that points out that Voyager has been there all of three days makes an appropriately biting statement against cultural imperialism, even given the dire situation). In splitting the difference between this character development, the environmental parable, and the genre collision, "Thirty Days" remains a breathtaking example of just how much can be combined into a single episode, work in its entirety, and still deliver a smart, well-paced plot. It's a bit of a neglected gem, but it deserves to be neglected no more, because this really is a brilliant episode of television.

Any Other Business:

• Ah yes, the old lag in his cell, telling his tale of woe on the high (well, low) seas. Everything I've written in the main review holds absolutely true, but I'm not sure it quite coveys just how much fun this episode really is.

• Robert Duncan McNeill is one of the reasons the episode works so well, because he really delivers one of his top-tier performances here. His wobbling sense of worth as to whether the letter is really worth writing is well worth pointing out, since it gives glimpses of the "old" Tom, petulant and immature, only to realize that he's actually developed enough maturity to listen to advise and take it. Really, really, excellent characterization.

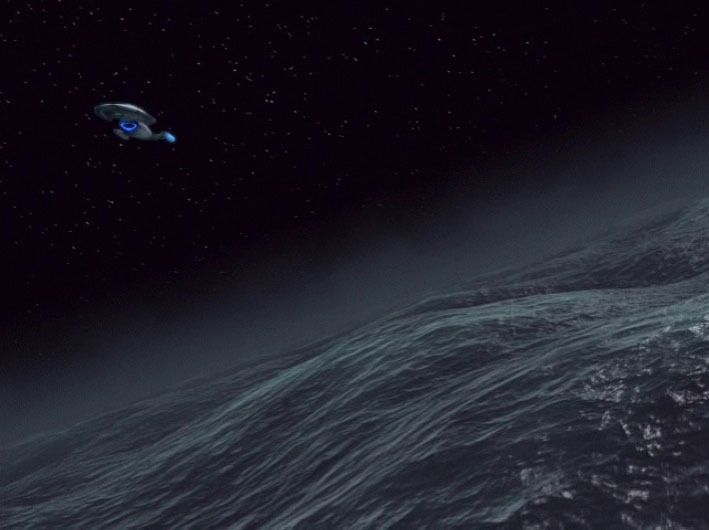

• Since I only talk about special effects when they are of real note, the ocean planet looks really good, and it's a powerful image of Voyager hanging over the crashing waves.

• For the one and only time in the entirety of Voyager we get to see the Delaney sisters.

• Janeway's punishment of demoting Tom and sentencing him to thirty days confinement doesn't really have any precedent that I can think of in Star Trek, yet it doesn't feel inappropriate, either, since it's clearly been taken from the genre collision side of things rather than the Trek side. And I love the way we get a scene where there's a big battle but it’s all over there, out of shot, a nice way to emphasize Tom's isolation and the fact that events carry on without him.

• Seven gets another one of her Borg jokes: "It is in my nature to comply with the Collective".

• Tom's beard grows incredibly slowly over the thirty days. I know there's "beard suppressor" as part of the spinoff material but I don't recall it ever being in-canon. When Tuvok finally releases him from captivity it looks like he's just about managed 5 O'clock shadow.

Season Five, Episode 10 - "Counterpoint"

Kiss Me, Kate

And so, as every principal character is gifted an episode in this season to show off their stuff, we now reach Janeway. Because the structure of this season has leaned towards giving individual characters their chance to shine we haven't had a lot from Janeway apart from her psychological issues back in "Night", so "Counterpoint" feels like a good time to re-engage with the character lest we forget who sits in the big chair, and yet it takes an approach that manages to feel rather new.

There's always a tension in Janeway's character that comes from her unique position as the only female lead in the show's history (thus far - maybe 2017 will change that). Janeway as a character has been most successful as a character who's written as a woman rather than a woman who's written as a character, and it's this that's allowed her to function so smoothly as the heart of Voyager's feminist agenda. Yet the one aspect of her character that's been skirted around is her romantic life. We've walked up to this line several times - the potential for romance with Chakotay in "Resolutions", the dissolution of her relationship with her fiancée as established in "Hunters" and so on - but she's never had a full-on romance. In way this makes sense - seen through the filter of 90s television giving her a romantic role runs the risk of reducing the character to a more typically "feminine" role rather than allowing her to stand on her own, so by holding off on this side of her character Janeway is allowed to be established as the equal of Picard and Sisko in terms of taking command before addressing this, more emotionally engaged, side of her character at a later date. And while you would be hard-pressed to call "Counterpoint" a full-on romance, it is equally the most direct approach to that side of Janeway's personality that we've seen for a very long time. What makes "Counterpoint" so brilliant (oh, and it really, really is brilliant) is that Janeway is never played for a fool, nor is her fairly overt romantic interest in Kashyk ever shown as weakness. Indeed, quite the reverse is true, because this episode is able to give Janeway the space to actually have feelings for someone while at the same time never allowing this to overwhelm her skill as a strategist. It's the final scene between her and Kashyk on the bridge that brings this home, her making it clear that, even as she wanted to believe in his change of heart, she wouldn't endanger her ship or the refugees just for that. That this scene is able to show off her strategic thinking without undermining the emotional centre of the episode and that it's also able to heighten Janeway's sense of loneliness without this ever tipping over into maudlin territory, shows a script which is really engaged with what it's trying to achieve.

But this would only work if we can believe that Kashyk is a plausible romantic partner for Janeway, and the fact that he is raises some very interesting questions. Why would Janeway fall for a clear fascist stand-in? This isn't a question that the episode allows us to find easy answers for, and indeed there is something quite unsettling about this being someone Janeway is apparently genuinely interested it. That slightly unsettling nature lends the episode the feeling of being ever so slightly off, which helps to contribute greatly to keeping the audience off-balance as to just how far this is going to go, to great effect. It's a question the episode is smart enough to raise, but not stupid enough to answer. But in addition to this there's a mild genre collision going on here, with Second World War influences seeping in all over the place. This collision is nowhere near as overt as it is in "Thirty Days", but there's no doubt that Kashyk is being cast as a Nazi stand-in (even his uniform is designed to look utilitarian and fascist), and the telepaths being smuggled to safety are obviously easy to read as Jews being smuggled out of Germany. And while this never develops into something as crass as Janeway's List that's clearly the direction the episode is leaning in. So if this is using aspects of the Second World War to drive the plot, then the "resistance girl" seducing the Nazi Kaptian is certainly a part of that genre, as we saw back in "The Killing Game", and it's clear that is at least in part what's going on here. Yet it's also clear that, for all the games she is playing Janeway really does develop some feeling for him, and vice versa. Kashyk's duty wins out, naturally, but there's real regret in his voice when he leaves the bridge at the end, and it's clear that, for all he's beaten, Janeway genuinely earns his respect in the way she handled the situation. As much as stargzing or sharing coffee over work this helps to sell the conflicted nature of their relationship, because it also shows that both of them ultimately remain loyal to their respective positions over their feelings, so Janeway will never give up her ship or the refugees for Kashyk, and Kashyk will never give up his hunt for her. This also manages to avoid falling into the cliché of "in another world we could have been friends" because it's really made clear that they wouldn't be - both are too entrenched in their relative positions for this ever to be the case. It's a more complex relationship than we're used to seeing played out over forty-five minutes, but then that's why it's so successful - it's the complexity that makes it register as real.

This isn't an episode which could be said to be "about" bigotry, but equally it's clear that everyone's actions are driven by it. It's an episode that begins in media res, albeit in a very soft sort of way, but the rescue of the telepaths here is clearly motivated by compassion on the part of the Starfleet crew and against the prejudice of the Devore Imperium. There's a sense of scale present again - we have an adventure that plays out over weeks, not hours or days, and we get to tool around this region of space a fair bit, which lends greater scope to events - but events are driven by the fleeing of the refugees. Indeed that contrast of scale held against the personal dance between Janeway and Kashyk, gives the episode an extra dimension, the personal played out against a large-scale backdrop. This also gestures towards the soft genre collision going on here, specifically invoking a different Second World War movie via the ghosts of Casablanca, with Rick's heartstrings being tugged in the titular city while Ingrid Bergman emotes in soft focus. Yet here we see an equally soft invocation of Voyager's continuing feminist inversion, with Janeway cast the Bogart role, the central character who loves and loses, but in line with an inversion the Ilsa role in "Counterpoint" is taken by the evil neo-fascist rather than a more straightforwardly sympathetic character. There may be no "beautiful friendship" by the end of the episode - well, not between Janeway and Kashyk anyway - but the conjuring of those distant ghosts gives "Counterpoint" just a little extra in terms of its execution, and help the thematic and emotional aspects of the script work together. Even the use of music here - sweeping Tchaikovsky and Mahler rather than the traditional in-house score - gives proceeding a more old-fashioned feel and evokes a different time and place altogether. It also acts as a good demonstration of what a difference a well chosen score can make - devoid of the usual sweep-upwards-to-end-of-act music that normally synchs up with the action we instead have classical pieces which linger or fade, leading the audience to ponder what they've seen, acting as musical ellipses rather than as full stops. These might seem like minor details but they all add atmosphere and resonance to everything that happens, and it's in these details that "Counterpoint really flourishes as an episode. Everything that we see and hear helps mark "Counterpoint" out as just that little bit different, that little bit special, and the final result ends up being something really special indeed. Here's lookin' at you, Kashyk.

Any Other Business:

• Obviously Kate Mulgrew is just wonderful here, turning in a nuanced, layered performance that shows both Janeway's more vulnerable side and just how clever she could be. But we shouldn't under-estimate Mark Harelik either, who turns in a wonderfully slimy performance as Kashyk. The way he spits out the name Prax is a joy to behold.

• Oh, and a nice yay for Star Wars fans - Kashyyyk being, naturally, the planet the Wookies come from. That doesn't add anything to this story, but it feels like a nice nod.

• Neelix gets to break out his parenting skills again, taking care of the telepathic children. The scene where he tells them a story, one reads his mind, then tells him not to is actually rather brilliant, because in a very, very short scene it confronts the bigotry that drives the Devore and manages to dismiss it in about three sentences flat.

• The side trip to find the scientist Torat who can help the crew find the moving wormhole is another nice example of an expanded scale, and Torat's reptilian inflation of sacs by his nose and cheeks when he's exasperated is surprisingly well realized. Though Janeway is a bit heavy-handed with him...

• Alexander Enberg as Vorik gets a mention in the post-titles credits, but appears on screen for all of about ten seconds and doesn't have a single line.

• Nice to hear Suder mentioned, another small but welcome piece of continuity.

• Kashyk coming to realize he's been defeated one revelation at a time feels incredibly satisfying, as does his spat out, "You created false sensor readings!" only for Janeway to calmly reply, "That is the theme for the evening, isn't it?"

• If this episode has one flaw, it's that Janeway is gambling big time that after Kashyk discovers he's been outsmarted he'll leave for fear of what will appear on his record, rather than have Voyager impounded.

Voyager To The Bottom Of The Sea

Genre tropes in fiction, as "Darkling" demonstrated, need more than just the existence of them within a specific episode to function or make their use worthwhile. Just empty repetition is boring - the basics of the genre are visible but if you don't do something interesting with them then it just looks like you're being lazy, that an episode has nothing else going for it so here, stick in these familiar bits, people will recognise it, and we can move on to something else. This is what I've referred to in the past as genre collision - taking the specifics of a certain type of story, in this case 19th century sea-faring adventure fiction, and colliding it with the world of Star Trek to see what happens, as "Thirty Days" does. The results, which are delightful, more than justify the exercise of genre collision here, and actually have something useful to say and add to our ongoing characters and stories.

Saying that, though, there's one thing that pretty much needs to be put aside at the beginning, and that is of course scientific plausibility. The episode does slightly gets away with this, because what we get here is, not for the first time this season, a narrative which is slightly left-of-centre, which is to say this is not being delivered by an omnipresent narrator as most episodes are, but instead events are being related to us via the perspectives of a single character. This means that what we get told about here isn't necessarily the literal truth of what happens but instead what Tom recalls, remembers, or otherwise makes up. He's trying to justify his behaviour to his father, but of course it's in the nature of self-justification to put oneself in the best light, and that includes the circumstances one finds oneself in. So while the ocean in space is an immediately striking image on its own, and we have no reason to doubt its veracity, later when Tom tries to stop a breach in the hull several hundred kilometres down by just putting his hands over the leak it looks silly (he, and indeed the Delta Flyer, would just implode). But this is just his way of telling the story, so the fact that it’s not a literal representation of the facts means the episode doesn’t need to commit to a sense of “real” reality in the way a standard episode would. While this helps paper over any number of implausible events, there's more than enough of Star Trek's own reality to conclude what we're being told is, if not 100% of the truth, at least close enough to make what we see here seem likely, so while Tom may be an unreliable narrator, he's not too unreliable. And though we hear specific mention made of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea, and though it's possible for the Delta Flyer to double as a Nautilus stand-in, events here actually have as much in common with that other great titan of 19th century sailing fiction, Treasure Island. The parallels are many, with the main part of the story here being told in "first person" (which is to say, by Tom) just as in Treasure Island; the central character of the narrative is also the person who is actually narrating the story; and you could even go so far as to suggest that the reactors under the ocean qualify as "buried treasure" (certainly their value to the Moneans is without parallel, and it is vague X shaped, as in "marks the spot"). And, if you really want to push it, Treasure Island is also a coming-of-age story, just as Tom "comes of age" by finding a cause to fight for that he genuinely believe in, rather than one he just drifted into looking for a fight, as with the Maquis (and the importance of it being B'Elanna who points this out to him shouldn't be missed either). Which is not to say that there aren't any parallels with Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea, because there are, most obviously with it's "fiction predicts the future" conceit; the famous giant cuttlefish battle being suggested by the massive "electric eel" the Flyer runs into on its first dive into the deep; and the fact that Nemo himself is often depicted as standing up for those who cannot defend themselves (which in this context is both the ocean itself and the Moneans who would otherwise suffer because of administrative inaction). The point of drawing all these parallels is to show just how steeped in the genre of 19th century fiction this is, while still functioning very much as a Star Trek story, because it's able to successfully update the iconography of the past to make it usefully function in the future.

Of course there's also the very 20th century aspect to the story as well, which is that it functions as a not-exactly-subtle environmental parable as well. The Mineans are exploiting the ocean for their own good which is bringing around the collapse of the very ecosystem they are dependant on for their survival. Not what you would call subtext, is it? Yet it's this inclusion that really makes the episode work as more than just a hollow genre pastiche because here we find one of the two reasons for the episode to exist. By functioning as an environment parable this isn't just fun and games that could just as easily have been done on the holodeck, it gives some actual stakes to the story, and by doing so gives a purpose to the borrowed iconography. Exploitation of the oceans was a big environmental issue in the 1990s, between oil spills (the most well known of which was the Exxon Valdez oil spill, which actually happened in 1989), whaling, fish being caught to the point of stocks collapsing, plastics pollution... doing a story specifically about an oceanic environment feels very 1990s, but in a representative way rather than doing a broader global warming or ozone layer-type story. So again we see the fit of the iconography and the story - a very 90's concern filtered through both the 19th and 24th centuries, while at the same time delivering an entertaining, engaging episode. And of course the use of Captain Proton here is also significant, this time taking early 20th century imagery and using that as a starting point for Tom's motivation to get involved - Tom's heartfelt, "no Captain Proton to the rescue this time" is the jumping off point for B'Elanna to push him just that little bit further, and of course Captain Proton is exactly the kind of adventure serial (along with Westerns) that Star Trek draws its roots from.

The final purpose of the episode is to give Tom some character development, and push him just that little bit further outside his comfort zone. Since his settling down with B'Elanna he's been a more stable character, still a little roguish but obviously better off for being in the relationship. Here we get to see him stretching out in more rebellious directions, again very much in line with the hero-of-his-own-story that both Jim Hawkins and Captain Nemo represent. We haven't had any specific mention of his interest in 19th century fiction before but this still feels perfectly in line with a character who tinkers with old cars on the holodeck and enjoys Captain Proton in his spare time. Certainly his interest in historical fiction feels character consistent, as does his expanded sense of responsibility. For all his joking with whatever character needs a line to be included in the episode while he's in solitary, it's clear from the actions that what we see here that this is a deliberate choice, and one he is willing to accept the consequences of. This is very far from the rash, impulsive character of earlier in the show and instead we see someone who's learned the lessons Janeway has been trying to teach - indeed, learned them all too well, so that his sense of responsibility overwhelms his sense of duty or his ability to follow orders. Yet this never pushes him into territory where you feel like the character is acting like an idiot for not just doing what he's damned well told, and this is, again not for the first time, because both his arguments and Janeway's arguments are correct. He's right that the Moneans clearly aren't going to do a thing to try and resolve the situation, and Janeway is right that it's not up to them to hector every society them come across into doing what they think (the Monean minister that points out that Voyager has been there all of three days makes an appropriately biting statement against cultural imperialism, even given the dire situation). In splitting the difference between this character development, the environmental parable, and the genre collision, "Thirty Days" remains a breathtaking example of just how much can be combined into a single episode, work in its entirety, and still deliver a smart, well-paced plot. It's a bit of a neglected gem, but it deserves to be neglected no more, because this really is a brilliant episode of television.

Any Other Business:

• Ah yes, the old lag in his cell, telling his tale of woe on the high (well, low) seas. Everything I've written in the main review holds absolutely true, but I'm not sure it quite coveys just how much fun this episode really is.

• Robert Duncan McNeill is one of the reasons the episode works so well, because he really delivers one of his top-tier performances here. His wobbling sense of worth as to whether the letter is really worth writing is well worth pointing out, since it gives glimpses of the "old" Tom, petulant and immature, only to realize that he's actually developed enough maturity to listen to advise and take it. Really, really, excellent characterization.

• Since I only talk about special effects when they are of real note, the ocean planet looks really good, and it's a powerful image of Voyager hanging over the crashing waves.

• For the one and only time in the entirety of Voyager we get to see the Delaney sisters.

• Janeway's punishment of demoting Tom and sentencing him to thirty days confinement doesn't really have any precedent that I can think of in Star Trek, yet it doesn't feel inappropriate, either, since it's clearly been taken from the genre collision side of things rather than the Trek side. And I love the way we get a scene where there's a big battle but it’s all over there, out of shot, a nice way to emphasize Tom's isolation and the fact that events carry on without him.

• Seven gets another one of her Borg jokes: "It is in my nature to comply with the Collective".

• Tom's beard grows incredibly slowly over the thirty days. I know there's "beard suppressor" as part of the spinoff material but I don't recall it ever being in-canon. When Tuvok finally releases him from captivity it looks like he's just about managed 5 O'clock shadow.

Season Five, Episode 10 - "Counterpoint"

Kiss Me, Kate

And so, as every principal character is gifted an episode in this season to show off their stuff, we now reach Janeway. Because the structure of this season has leaned towards giving individual characters their chance to shine we haven't had a lot from Janeway apart from her psychological issues back in "Night", so "Counterpoint" feels like a good time to re-engage with the character lest we forget who sits in the big chair, and yet it takes an approach that manages to feel rather new.

There's always a tension in Janeway's character that comes from her unique position as the only female lead in the show's history (thus far - maybe 2017 will change that). Janeway as a character has been most successful as a character who's written as a woman rather than a woman who's written as a character, and it's this that's allowed her to function so smoothly as the heart of Voyager's feminist agenda. Yet the one aspect of her character that's been skirted around is her romantic life. We've walked up to this line several times - the potential for romance with Chakotay in "Resolutions", the dissolution of her relationship with her fiancée as established in "Hunters" and so on - but she's never had a full-on romance. In way this makes sense - seen through the filter of 90s television giving her a romantic role runs the risk of reducing the character to a more typically "feminine" role rather than allowing her to stand on her own, so by holding off on this side of her character Janeway is allowed to be established as the equal of Picard and Sisko in terms of taking command before addressing this, more emotionally engaged, side of her character at a later date. And while you would be hard-pressed to call "Counterpoint" a full-on romance, it is equally the most direct approach to that side of Janeway's personality that we've seen for a very long time. What makes "Counterpoint" so brilliant (oh, and it really, really is brilliant) is that Janeway is never played for a fool, nor is her fairly overt romantic interest in Kashyk ever shown as weakness. Indeed, quite the reverse is true, because this episode is able to give Janeway the space to actually have feelings for someone while at the same time never allowing this to overwhelm her skill as a strategist. It's the final scene between her and Kashyk on the bridge that brings this home, her making it clear that, even as she wanted to believe in his change of heart, she wouldn't endanger her ship or the refugees just for that. That this scene is able to show off her strategic thinking without undermining the emotional centre of the episode and that it's also able to heighten Janeway's sense of loneliness without this ever tipping over into maudlin territory, shows a script which is really engaged with what it's trying to achieve.

But this would only work if we can believe that Kashyk is a plausible romantic partner for Janeway, and the fact that he is raises some very interesting questions. Why would Janeway fall for a clear fascist stand-in? This isn't a question that the episode allows us to find easy answers for, and indeed there is something quite unsettling about this being someone Janeway is apparently genuinely interested it. That slightly unsettling nature lends the episode the feeling of being ever so slightly off, which helps to contribute greatly to keeping the audience off-balance as to just how far this is going to go, to great effect. It's a question the episode is smart enough to raise, but not stupid enough to answer. But in addition to this there's a mild genre collision going on here, with Second World War influences seeping in all over the place. This collision is nowhere near as overt as it is in "Thirty Days", but there's no doubt that Kashyk is being cast as a Nazi stand-in (even his uniform is designed to look utilitarian and fascist), and the telepaths being smuggled to safety are obviously easy to read as Jews being smuggled out of Germany. And while this never develops into something as crass as Janeway's List that's clearly the direction the episode is leaning in. So if this is using aspects of the Second World War to drive the plot, then the "resistance girl" seducing the Nazi Kaptian is certainly a part of that genre, as we saw back in "The Killing Game", and it's clear that is at least in part what's going on here. Yet it's also clear that, for all the games she is playing Janeway really does develop some feeling for him, and vice versa. Kashyk's duty wins out, naturally, but there's real regret in his voice when he leaves the bridge at the end, and it's clear that, for all he's beaten, Janeway genuinely earns his respect in the way she handled the situation. As much as stargzing or sharing coffee over work this helps to sell the conflicted nature of their relationship, because it also shows that both of them ultimately remain loyal to their respective positions over their feelings, so Janeway will never give up her ship or the refugees for Kashyk, and Kashyk will never give up his hunt for her. This also manages to avoid falling into the cliché of "in another world we could have been friends" because it's really made clear that they wouldn't be - both are too entrenched in their relative positions for this ever to be the case. It's a more complex relationship than we're used to seeing played out over forty-five minutes, but then that's why it's so successful - it's the complexity that makes it register as real.

This isn't an episode which could be said to be "about" bigotry, but equally it's clear that everyone's actions are driven by it. It's an episode that begins in media res, albeit in a very soft sort of way, but the rescue of the telepaths here is clearly motivated by compassion on the part of the Starfleet crew and against the prejudice of the Devore Imperium. There's a sense of scale present again - we have an adventure that plays out over weeks, not hours or days, and we get to tool around this region of space a fair bit, which lends greater scope to events - but events are driven by the fleeing of the refugees. Indeed that contrast of scale held against the personal dance between Janeway and Kashyk, gives the episode an extra dimension, the personal played out against a large-scale backdrop. This also gestures towards the soft genre collision going on here, specifically invoking a different Second World War movie via the ghosts of Casablanca, with Rick's heartstrings being tugged in the titular city while Ingrid Bergman emotes in soft focus. Yet here we see an equally soft invocation of Voyager's continuing feminist inversion, with Janeway cast the Bogart role, the central character who loves and loses, but in line with an inversion the Ilsa role in "Counterpoint" is taken by the evil neo-fascist rather than a more straightforwardly sympathetic character. There may be no "beautiful friendship" by the end of the episode - well, not between Janeway and Kashyk anyway - but the conjuring of those distant ghosts gives "Counterpoint" just a little extra in terms of its execution, and help the thematic and emotional aspects of the script work together. Even the use of music here - sweeping Tchaikovsky and Mahler rather than the traditional in-house score - gives proceeding a more old-fashioned feel and evokes a different time and place altogether. It also acts as a good demonstration of what a difference a well chosen score can make - devoid of the usual sweep-upwards-to-end-of-act music that normally synchs up with the action we instead have classical pieces which linger or fade, leading the audience to ponder what they've seen, acting as musical ellipses rather than as full stops. These might seem like minor details but they all add atmosphere and resonance to everything that happens, and it's in these details that "Counterpoint really flourishes as an episode. Everything that we see and hear helps mark "Counterpoint" out as just that little bit different, that little bit special, and the final result ends up being something really special indeed. Here's lookin' at you, Kashyk.

Any Other Business:

• Obviously Kate Mulgrew is just wonderful here, turning in a nuanced, layered performance that shows both Janeway's more vulnerable side and just how clever she could be. But we shouldn't under-estimate Mark Harelik either, who turns in a wonderfully slimy performance as Kashyk. The way he spits out the name Prax is a joy to behold.

• Oh, and a nice yay for Star Wars fans - Kashyyyk being, naturally, the planet the Wookies come from. That doesn't add anything to this story, but it feels like a nice nod.

• Neelix gets to break out his parenting skills again, taking care of the telepathic children. The scene where he tells them a story, one reads his mind, then tells him not to is actually rather brilliant, because in a very, very short scene it confronts the bigotry that drives the Devore and manages to dismiss it in about three sentences flat.

• The side trip to find the scientist Torat who can help the crew find the moving wormhole is another nice example of an expanded scale, and Torat's reptilian inflation of sacs by his nose and cheeks when he's exasperated is surprisingly well realized. Though Janeway is a bit heavy-handed with him...

• Alexander Enberg as Vorik gets a mention in the post-titles credits, but appears on screen for all of about ten seconds and doesn't have a single line.

• Nice to hear Suder mentioned, another small but welcome piece of continuity.

• Kashyk coming to realize he's been defeated one revelation at a time feels incredibly satisfying, as does his spat out, "You created false sensor readings!" only for Janeway to calmly reply, "That is the theme for the evening, isn't it?"

• If this episode has one flaw, it's that Janeway is gambling big time that after Kashyk discovers he's been outsmarted he'll leave for fear of what will appear on his record, rather than have Voyager impounded.