Post by Prole Hole on Jun 30, 2016 13:25:22 GMT -5

Season Seven, Episode 8 - "Nightingale"

"... and the Pirelli's are going to cost extra..."

Of all the principal characters in Voyager, Harry has by far the least development of any of the regulars, especially the B-cast, and we're up to Season Seven now so he's running out of time. Neelix had his relationship with Kes and the eventual establishment of his independence, Kes herself got to go off and join another realm after a three-season arc of self-actualization, we've had plenty of background character details on Chakotay... What's Harry had? The staggeringly forgettable "Non Sequitur" and that's about it. That's made him a tricky character to get much of a handle on, and though Wang has gotten better over the last season or two at playing the role it's taken a long time to get to the point where we're expected to care about what happens to him. The string of Harry-meets-the-wrong-woman episodes haven't exactly helped his case, but there have been rare examples - "Timeless", for one – that shows how the character can work, and how Wang is able to work effectively on the few occasions when his strengths are actually written towards. While "Nightingale" doesn't push him in the same direction as "Timeless" it is, at least, an episode that doesn't rely on him having some doomed romance nobody gives two figgins about, and sets about highlighting a character trend you would think would have been an obvious one to go to from the start yet has hardly ever been addressed, which is his ambition.

Now that's not to say we've never had any glimpses of it, because there has been the odd occasion where he's tries to assert himself, but that's the thing – they've just been glimpses. It's a strange side of his character not have really come up because, back in "Caretaker", he's actively presented as the Bright Young Thing of the Voyager crew, all shiny and new and raring to go, and those characteristics are intentionally contrasted with Tom's more worldly-wise side. Given that most of the original, non-Maquis members of the crew were fairly young to begin with, that makes him stand out even amongst the regulars, and it's not hard to imagine a potentially interesting back-story as to how he got to a position on the bridge at such a young age. This never arrives, and the failure to capitalize on such an obvious part of who Harry is feels, now that we actually get to explore some of that, like an obvious waste. Harry has a strong desire to command, to be a captain one day, we're told here, and to be fair we've had a couple of episodes when he's been in command of the night shit, so it's not completely out of the blue, even as it's not really been explored yet. This all makes perfect sense for an ambitious, energetic, enthusiastic ensign whose career comes to an abrupt stop thanks to an unscheduled trip to the Delta Quadrant, a point he himself makes when lamenting to Janeway that back home he'd be a Lieutenant by this point in his career. That's bound to be frustrating for him, and the way-too-late-in-the-day decision to actually do something with this leads to Harry getting his first real command, even if doing it on an alien ship was likely not what he originally intended. This is all good, solid groundwork for Harry, and if it is way too late in the day, it's still a case of better late than never. And the nature of command and the way it challenges his own preconceptions about himself is the sharpest piece of character observation "Nightingale" has about him, and the sharpest we've had about him likely since "Timeless", or maybe even "The Chute". It's easy to imagine oneself in charge, decorating your own ready room and sitting in the Big Chair, but of course the reality is never going to be that simple. Harry's in-built sense of enthusiasm and (slightly brittle) self-belief make the realization of his failing strike home, and in this it's smart to pair him with Seven. Whatever else Seven will do she definitely won't molly-coddle him and forcing him to confront the reality of their situation head on, where say someone like Tom might have lent a more sympathetic but ultimately less helpful ear, gives her a useful role to play which goes beyond just propping up the lead character. Harry remains the primary focus, but using her long-established bluntness as a way to motivate him means her actions are still rooted in the character we know.

There's two other things this episode does right by Harry and they can be ticked off pretty straightforwardly. He never becomes a peril monkey, and he never has a romance. Sounds simple doesn’t it? Yet it makes a world of difference to see him in a context that removes the two most common and least successful usages of the character, and which actually gives him room to breathe. Wang makes good use of this opportunity and turns in an above-average performance for him. The better, slightly tweaked version of the character comes to the fore and there's not a single scene where he's anything less than fine, even when bits of the material aren't. The problem – you knew there was going to be a problem – is that a fair chuck of the script is pretty rote. Harry's placed in command, it doesn't go as expected, he has a crisis of confidence, but pulls through in the end to save the day. That's all very familiar, and though laying it out bare like that does a bit of a disservice to the episode, it's hard to get away from the fact that a lot of the beats are just too overly familiar to really work. We even get a version of "but someone died on my watch!", which fine, that can be traumatic the first time it happens, but this isn't an episode with the time to burn on really exploring that. So while it's not something that's just forgotten about it's also not something given enough time to properly register and as such it can't achieve what it sets out to. It's a valid character beat but it's presented far too literally and it doesn't impact enough to carry the weight it's clearly supposed to. The predictability of this is really the worst sin the episode commits, and it's a biggie because it's undermining a lot of the solid work which would otherwise have more of chance to flourish. It's the same old Problem Of Harry – even when things seem to be going well for him there's always something lurking that gets in the way.

But even given this, I don't want to end by suggesting "Nightingale" is bad, really. It makes a real attempt to engage with the actuality of who Harry is and does more work, and more successful work, than we've seen for him in a good season and a half, and possibly much longer. It's too much to hope that one episode could course-correct over six seasons' worth of neglect and general mishandling of one character, but at least it's a positive step in the right direction, and in return we get strong performances from all involved. This week's warring aliens aren't drawn especially vividly, but neither are they a complete bust either – the blockaded planet is an interesting-in-theory development (though don't maybe examine it too closely), and if the bait-and-switch of the vaccine actually turning out to be about smuggling technology instead isn't particularly original, the script deserves points for keeping the Kraylor actually sympathetic and still on a mission of mercy, just not the one Harry thought they were on. It would have been much more clichéd if they had turned out to be the (gasp!) bad guys all along, so by keeping them on-side we at least get a slight change to the formula. OK, sure, it's not massive but at least it's something, and it's balanced by Janeway basically being taken in by the Annari. So let's on this occasion err on the side of generosity and forgive the largely obvious direction of the script in favour of giving a somewhat neglected character his little moment in the limelight. This is actually Harry's final lead in the series, he doesn't take centre stage in any more episodes, and if we come to it too late (and we do come to it too late) then let's just be glad that this his final episode and not some tedious doomed romance. Because, whatever flaws there are in this episode, we know from experience that things could be so very much worse.

Any Other Business:

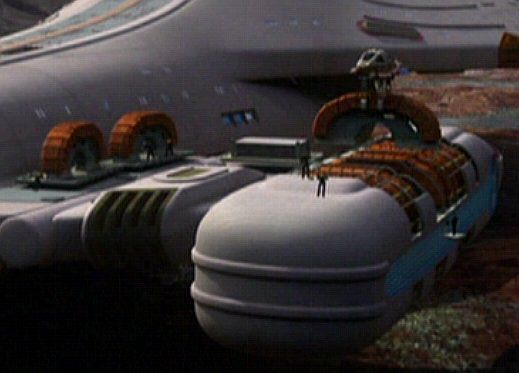

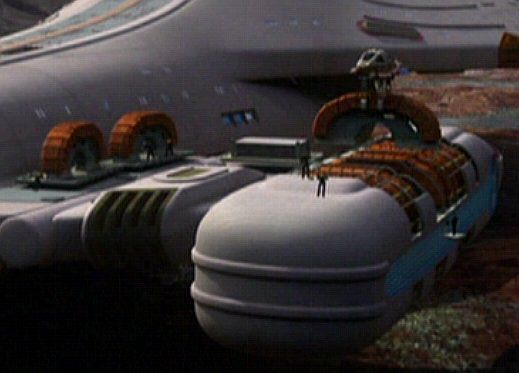

• One of the great things about this episode is that it actually makes the effort to land Voyager on a planet and takes the time to show the crew repair it – we even get to see people climbing over the warp engines! It's a great touch, and again is a case of special effects enhancing, in this case, the realism of a ship in long-term deep space which requires physical maintenance.

• But while that's a vote in the plus column, in the minus column we have the whole sub-plot about Icheb mistaking B'Elanna's concern for him as romantic interest. It doesn't really serve any purpose (beyond giving B'Elanna and Icheb some lines this week) and while it's never badly acted or anything it's also a typical Star Trek B-story that contributes nothing other than five minutes of screen time.

• Though we don't get a Captain Proton scene, Harry using it as an example ("I always get to play Buster Kincaid") is a good use of the holodeck program to illustrate the point he's making, and one the character would use, so it's a decent piece of writing.

• Why does Harry have a sax with him on a stand in his ready room, when he plays the clarinet?

• Fine, so it turns out the Kraylor are smuggling a cloaking device, not medical supplies. But did it not occur to anyone to check out their story? What if they'd be running weapons or people smuggling or something?

• The most frustrating aspect of this episode remains the fact that we should have got it back in Season Two, where the more rote aspects of the script could have been forgiven if it were the start of a character arc for Harry, rather than being apologized for at the end (and I'm sure it would have been better than all that mucking about with Seska).

• Some good writing for Seven in amongst all this, with her "oh get over yourself" attitude providing a refreshing contrast to Harry's doubts.

• Which is as well, because the "mutiny" is the one part of this episode that absolutely doesn't work, never rising about cliché, and resolving waaaay to quickly to be an effective plot beat.

• Yes about that blockaded planet. Loken states that his people desperately need the cloak because the Annari are blockading their planet and they need it to get food to their people. But this is a planet, not some island with a couple of gunboats hanging off it's only port. Why can't they grow food? Are they overpopulated, was their an environmental catastrophe, is there something else? We could have done with a bit more details here to explain this.

• But it all ends on a fairly positive note for Poor Old Harry, which makes a nice change for him.

Season 7, Episode 9 / 10 - "Flesh And Blood"

Killing In The Name Of...

If "Flesh And Blood" is about anything, it's about perspective. Oh, and consequences. Oh, and responsibility. A far cry from the hollow emptiness that so dogged "Unimatrix Zero", "Flesh And Blood" roars the Voyager two-parter back into life while following up on the thematic work that's already been laid down in the season so far. Let's take stock on some of these ideas, shall we?

1) Perspective. It's everything here. And really for the first time since we've met the Hirogen we get an alternative perspective on them, which is to say we get to see a Hirogen who isn't a hunter. We get to see the consequences of involving someone rather less committed to their way of life than any other member of the Hirogen we have met, but it means we have an insider providing perspective. The Doctor fulfils this role for the holograms too – an outsider perspective on a species (if we can refer to the holograms that way) the person providing that perspective is a member of.

2) Consequences. Well this is really the centre of the non-hologram arc here. Most straightforwardly we have the consequences of Janeway giving the Hirogen the holo-technology. What they have chosen to do with it perhaps reflects what we might expect of the Hirogen – we know they're a hunting species, therefore they use the technology of the holograms to hunt. Fair enough, that was the point in giving them the technology in the first place. Yet we see a trait from Janeway here which ties in with the events of "Night" - that is to say, she apparently intentionally misremembers the events of "The Killing Game" in order to hold herself responsible and to an unattainable standard, just as in "Night" she misremembered the events of "Caretaker" to make herself seem more responsible. Here, she talks about the consequences of giving the Hirogen the holo-technology, and the danger that has put people in, apparently neglecting to remind herself that, at the end of "The Killing Game", bartering the holo-technology was the only thing that prevented the Hirogen and the crew of Voyager from slaughtering each other. So she did it to survive, in other words, rather than as a traditional trade of bargain. This is clearly part of Janeway's emotional make-up – she blames herself for the consequences of what happened, even though there was nothing else she could do. Which leads us nicely into...

3) Responsibility. This is clearly the flip-side of consequences. Janeway feels responsible for what happened because she gave away the holo-technology. The Doctor is responsible for B'Elanna's kidnapping. Donik, the Hirogen technician, is responsible for the holograms becoming more sophisticated than the hunters can deal with. What's telling in "Flesh and Blood" is that only those who face up to their responsibility and accept it are able to survive the episode. The Doctor is eventually able to admit his mistakes and move past the problems he causes. The Hirogen are able to move past their species-default of hunters to survive (well, some of them at any rate). But the person who doesn't survive – who can't survive – is Iden. He casts himself in the role of a saviour (and in this case the saviour) but is unable to accept the responsibility of that role and the weight that comes with it. As a result he is the sole hologram who doesn't make it to the closing credits. Even the Hirogen were able to overcome their instincts to hunt to the exception of all else, but given the chance to properly expand who and what he is he falls measurably short, and gets killed as a result.

So yes, there we go. Three straightforward thematic aspects all sit nicely on the surface, yet these's so very much more going on here, and in the development of these themes we start to see an emerging aspect of this season, one which was first hinted at during "Critical Care" and again in "Body And Soul", which is the way holograms are treated. In "Critical Care" the Doctor was seen as something owned, a piece of technology that was bought and sold as any other might be, though there were also - admittedly very low down in the mix - allusions to slavery in the imprisoning of someone and forcing them to work against their will (and note that in that episode people mostly treat the Doctor as someone who can be addressed as an equal, even as he's being exploited). The treatment of holograms as a rights issue is made more explicit in "Body And Soul", with the way holograms are referred to being much more directly equivalent with slavery, right up to the clichés of slavery (the whole "we even let them live in our house and they were still ungrateful!" speech that Jaryn gives the Doctor). "Flesh And Blood" (and again, note the similarity of names between these two episodes) makes this issue more explicit still, this time drawing a direct comparison with slavery rather than an allusion to it, with Iden referring to himself as a liberator of people chained by their organic creators, and of course his holy-man delusions meeting with his desire to lead the his people out of chains, as in Moses. But while "Flesh and Blood" makes the comparison with slavery explicit it also opens this up to other interpretations - the Civil Rights movement of 1960s America, the battle for gay rights, the fight for female equality – all while remaining focussed on providing a look at the schizoid dichotomy between what Iden wants to achieve (and its apparently noble goals) and his own increasingly delusional and unhinged reality. One of the things that’s become explicit over the course of Voyager is the way the Doctor functions as an emergent intelligence, and here we see the same things happening to the modified holograms the Hirogen have, with everyone treating them as basically equal to the Doctor and thus deserving of the same status and rights as the Doctor (the Voyager crew do this reflexively, and without having to have the details explained to them). Quite apart from the implicit suggestion that the Federation is on the brink of unintentionally creating potentially huge numbers of intelligences (essentially a new species), this gives weight to the moral arguments surrounding how Iden, the Hirogen and the Voyager crew see the holograms, yet we also get to see another set of holograms, who are very definitely not cut from the same emergent intelligence cloth. In a way, this feels like a curious step – since this is ostensibly about the rights of fully sentient holograms, why introduce a bunch of holograms who are not? In one sense the answer is obvious – they show the mania that Iden is succumbing to as his messiah complex takes over and he kills real sentient beings for a handful of holograms who are demonstrably not. Yet in another sense it also sets a sort of standard by which we can judge everyone else's reactions to what happens as well. By exhibiting compassion for the murdered (and entirely innocent) ship's captain that Iden kills we get to see the Doctor gradually return to the person we know rather than the convert he became, and we see the impact it has on Kegal and the other holograms. Or to put it another way – it provides a moral perspective on what's going on.

Because, as I mentioned, perspective is everything here. Almost everything exists in "Flesh and Blood" to provide perspective on something else, and those holograms are just one example which nevertheless serves to demonstrate a larger point. The obvious perspectives – the way Donik reflects an alternative perspective on what we assume Hirogans will be like, for example – help colour and shade in the details of everything that happens here, and by forcing the audience to reassess their assumptions as regards characters or motivations it means the episode can find real traction in what it's trying to deliver. Because, for all that I've said that perspective is everything, what the episode is really trying to deliver here is the fairly straightforward idea of not making assumptions and not allowing prejudice to blind decision making. That's obviously a very Star Trek theme, and by invoking a religious aspect, specifically the Bajoran religion, the episode is able to rise above some didactic lecture about how things aren't always what they seem. Indeed the profound moral ambiguity of a devout religious leader is here used as a deliberate attempt to destabilize the viewers' expectations, so while Iden starts off being a comparatively sympathetic character it's his religious zeal and fanaticism that eventually leads to his downfall. This isn't positied as a criticism of religion – again, this is extremely important to avoid the episode becoming hectoring – but is instead merely present as an example of someone so blinded by their own conceit they cannot see how far from their own path they have strayed. This is, obviously, a parallel with what the Doctor goes through, as he shifts from sympathy for the plight of the holograms, to outright convert to their cause, to Doubting Thomas (more religious parallels, then), to eventual rebel. The Doctor is, ultimately, able to maintain his sense of perspective and that eventually leads him to be true to himself and make the right call, rather than losing himself to extremism and zealotry. This paralleling of the Doctor and Iden is really the core of the episode's character work, and also delivers one of its most effective, and shocking, moments.

Because remember back in "Critical Care" I mentioned one of the key moments that the Doctor goes through is intentionally inflicting an illness on someone else, and how this essentially became the equivalent of him breaking his own Prime Directive? Well, there you could argue a bit, maybe, perhaps, if you squint a bit, that he had a moral justification for it, because he committed a small act of suffering to alleviate a much greater one. This is a slippery slope argument – the ends justify the means – but the point there wasn't whether the Doctor did the right thing or not, but rather that he was capable of doing it at all. That's fitting, since that episode stood as the functional start of the "rights of holograms" arc that's now occupied three stories this season (and will be back as the season progresses), and as "Flesh And Blood" picks up and expands on the rights theme so it also picks up and expands on what it is the Doctor is capable of. Because here he outright kills someone. There's no workaround to this – the story has spent two episodes making it clear that these holograms who have been freed from the Hirogen are people, not tools, or anomalies, or any other fudge, but sentient creatures deserving of rights and respect, and the Doctor actively guns one down. You could argue that, after beaming down to the planet with a bloody big gun, deprived of his mobile emitter, and after having basically been made out to be a fool for trusting Iden in the first place, the Doctor is pushed to a place where his actions seem, if not justifiable, then certainly not difficult to understand, but as with "Critical Care" the point here is that the Doctor is capable of doing this at all. Whatever shackles his program might once have held over him have truly been cast off now. He is free to do and act in the same way any organic might, and there's not a single reference to "ethical subroutines", which seems somewhat telling. And what he does with this freedom is kill someone (it's worth mentioning that it’s is possible to argue the Doctor didn’t know that Iden's program would be damaged beyond recovery so shooting him was a calculated risk, but that's not how it plays out on screen and Piccado essays the role as the Doctor being able to step up and take punitive action, without any excuses for his actions). This obviously gives us an entirely new perspective on the Doctor, and unlike "Critical Care" the Doctor doesn't, in the episode's final scene, try and make excuses about corrupt programming or whatever. He accepts the responsibilities for his actions, and is prepared to deal with this. Again, apart from separating him from Iden who was never prepared to face the consequences of what he did, this forces the audience to actively change the way they see the Doctor – that's why Janeway's comments at the end are more about acknowledging what it is the Doctor has gone through than it is about a more traditional sense of punishment (though if she really is going to treat the Doctor as an equal, I hope she does take away his emitter, since the Doctor is right – this would be an equivalent punishment to one of the regular crewmembers, just like we saw Tom confined to the brig during "Thirty Days"). For a character who has spent so much time being gradually whittled back to comic relief it's a bracing reminder of just what's possible with him when he's handled correctly.

The Hirogen have always been one of the most interesting and effective recurring species in the Delta Quadrant, and it's no real spoiler that this is their last big hurrah (there's going to be a lot of this over the remainder of the season, naturally). "The Killing Game" wasn't an episode that necessarily demanded a sequel, but the fact that we get one, and get to truly follow through on the consequences of both Janeway's and the Hirogen's decisions there makes "Flesh And Blood" stand out, especially since this is the only time a non-hunter is seen. Part of the reason that they remain effective is that they are not reduced to a series of clichés – we have a standard-issue growly Klingon hologram on hand in this story to show us what this can look like by way of contrast, helpfully – but rather remain cunning and, above all, intelligent. Neelix gets to do a little reverse psychology on them at the end of the second episode – what version of the story will get told? - but the point of the Beta understanding this and allowing his mind to be changed is not that he's easily manipulated by a wily Talaxian, but rather that he's smart enough to understand when it's necessary to change a point of view, when faced with compelling evidence to do so. It's not difficult to see how this feeds into the themes in the rest of the episode, but importantly by not resorting to type they Hirogen are given an additional dimension which doesn't in any way reduce their effectiveness or their status as a threat. Had this not turned out to be their final appearance the events of this episode would not in any way change the fact that they're still a dangerous, smart and cunning enemy, while still acknowledging that there's a lot more to them than just that. It's for this reason that the inclusion of Donik is so important, and why it's important that he's able to make it all the way to the closing theme tune. He's a symbol of everything this episode is trying to achieve, because just like the other Hirogen he's intelligent, capable and, like the Kaptian of "The Killing Game", blessed with enough foresight to understand that just continuing the way things have always been isn't good enough and that to survive one must change. But he's also representative of the arguments that the episode is putting forward, in a way just as much as the Doctor is. He's able to find a purpose for himself in changing, no longer a slave to the whims of an Alpha (and obviously the word slave there is chosen very deliberately) but instead able to break free and find his own path forward. Well, that's pretty clear, isn't it? In choosing to help the holograms, without coercion or favour, he comes to represent the point of this story. Just as the Doctor earns his freedom by acting in a way that demonstrates that he is capable of that freedom so Donik does the same. A thematically fulfilling, thoughtful and considerate episode, "Flesh And Blood" ultimately turns out to be the best two-parter Voyager has delivered in ages, and it certainly stands comparison against "Equinox" (truthfully, the only one to have come close to the standards set by "Year Of Hell" and "Scorpion"). As ever with these reviews there's plenty of things I've not been able to cover yet, not least of which is the fact that this, all thematic contortions aside, another absolutely fantastic entry into the action-adventure side of Voyager, and we have a production that's full of pace, energy and a real, tangible sense of threat. At this stage, in the long run up to the end of the series, it's both surprising and incredibly pleasing to have something as good as this, and something which is making real, material progress with a character when more typically we'd be expecting a greatest hits package as we get ever nearer "Endgame". There's life in the old dog yet.

Any Other Business:

• This episode was shown as a feature-length movie rather than as a two-parter over two weeks. The last story to do that was "Dark Frontier" (this is better).

• The opening sequence, with the Hirogen hunting the Starfleet holograms, and them turning the tables by opening fire from underwater, is quite brilliant. And, rather than the Garden Centre Of Doom, this is shot on location, and the difference between similar firefights ("Memorial", for example) which are studio-bound is dramatic. It's all just so much better when shot on location.

• The whole holo-ship is great, vaguely reminiscent of the one in Star Trek: Insurrection though somewhat more dangerous...

• Iden is an excellent character – a self-important, somewhat deluded person who crosses the line from sympathetic and exploited to insane, all without any eye-rolling or scenery chewing. It's a great performance too, and the character works incredibly well, especially when compared to the attempts in "Repression" to do something similar with a Bajoran religious fundamentalist.

• Equally Donik is a lovely character, and it's so great and refreshing to see another side to the Hirogen so they're not just presented as a culture with a single interest and nothing else.

• The Doctor's conversion to the cause does maybe come just a little bit too quickly, but if it does it's a very minor mistake. His trusting the shield frequencies to Iden is perhaps a bit stupid though (from a character perspective I mean, not from the writing).

• The through-line of B'Elanna's abduction and her trying to overcome her own prejudice and work with someone who looks like a Cardassian is very nicely handled, as is B'Elanna's repeated assertions about just how important engineers are. This is two intelligent, understanding female characters working their way through opposing points of view, and it makes a great counter-balance to all the testosterone sloshing about between the Hirogen, the Doctor and Iden. The thematic parallel of B'Elanna overcoming her own prejudice should also be perfectly obvious.

• Along the same lines, the inevitable praise for Roxann Dawson, who's as brilliant as ever.

• Speaking of females – we never once see a female Hirogen. I wonder how they procreate?

• The idea of Voyager hiding in the wake of the Hirogen ship is a bit daft, but it works pretty well on-screen (and with some generally terrific special effects). Though Janeway's bloody lucky there are no windows in the back of that Hirogen ship or the plan could have come crashing down very quickly.

• The Doctor killing Iden is a genuinely shocking moment, and handled really, really well on screen. Kudos to the writers for giving him the chance to go there.

• And it all ends surprisingly constructively. Donik gets a chance to undo some of the damage he's done, the holograms gain a measure of freedom, the Hirogen learn a valuable lesson, and the Doctor gets to grow as a character.

"... and the Pirelli's are going to cost extra..."

Of all the principal characters in Voyager, Harry has by far the least development of any of the regulars, especially the B-cast, and we're up to Season Seven now so he's running out of time. Neelix had his relationship with Kes and the eventual establishment of his independence, Kes herself got to go off and join another realm after a three-season arc of self-actualization, we've had plenty of background character details on Chakotay... What's Harry had? The staggeringly forgettable "Non Sequitur" and that's about it. That's made him a tricky character to get much of a handle on, and though Wang has gotten better over the last season or two at playing the role it's taken a long time to get to the point where we're expected to care about what happens to him. The string of Harry-meets-the-wrong-woman episodes haven't exactly helped his case, but there have been rare examples - "Timeless", for one – that shows how the character can work, and how Wang is able to work effectively on the few occasions when his strengths are actually written towards. While "Nightingale" doesn't push him in the same direction as "Timeless" it is, at least, an episode that doesn't rely on him having some doomed romance nobody gives two figgins about, and sets about highlighting a character trend you would think would have been an obvious one to go to from the start yet has hardly ever been addressed, which is his ambition.

Now that's not to say we've never had any glimpses of it, because there has been the odd occasion where he's tries to assert himself, but that's the thing – they've just been glimpses. It's a strange side of his character not have really come up because, back in "Caretaker", he's actively presented as the Bright Young Thing of the Voyager crew, all shiny and new and raring to go, and those characteristics are intentionally contrasted with Tom's more worldly-wise side. Given that most of the original, non-Maquis members of the crew were fairly young to begin with, that makes him stand out even amongst the regulars, and it's not hard to imagine a potentially interesting back-story as to how he got to a position on the bridge at such a young age. This never arrives, and the failure to capitalize on such an obvious part of who Harry is feels, now that we actually get to explore some of that, like an obvious waste. Harry has a strong desire to command, to be a captain one day, we're told here, and to be fair we've had a couple of episodes when he's been in command of the night shit, so it's not completely out of the blue, even as it's not really been explored yet. This all makes perfect sense for an ambitious, energetic, enthusiastic ensign whose career comes to an abrupt stop thanks to an unscheduled trip to the Delta Quadrant, a point he himself makes when lamenting to Janeway that back home he'd be a Lieutenant by this point in his career. That's bound to be frustrating for him, and the way-too-late-in-the-day decision to actually do something with this leads to Harry getting his first real command, even if doing it on an alien ship was likely not what he originally intended. This is all good, solid groundwork for Harry, and if it is way too late in the day, it's still a case of better late than never. And the nature of command and the way it challenges his own preconceptions about himself is the sharpest piece of character observation "Nightingale" has about him, and the sharpest we've had about him likely since "Timeless", or maybe even "The Chute". It's easy to imagine oneself in charge, decorating your own ready room and sitting in the Big Chair, but of course the reality is never going to be that simple. Harry's in-built sense of enthusiasm and (slightly brittle) self-belief make the realization of his failing strike home, and in this it's smart to pair him with Seven. Whatever else Seven will do she definitely won't molly-coddle him and forcing him to confront the reality of their situation head on, where say someone like Tom might have lent a more sympathetic but ultimately less helpful ear, gives her a useful role to play which goes beyond just propping up the lead character. Harry remains the primary focus, but using her long-established bluntness as a way to motivate him means her actions are still rooted in the character we know.

There's two other things this episode does right by Harry and they can be ticked off pretty straightforwardly. He never becomes a peril monkey, and he never has a romance. Sounds simple doesn’t it? Yet it makes a world of difference to see him in a context that removes the two most common and least successful usages of the character, and which actually gives him room to breathe. Wang makes good use of this opportunity and turns in an above-average performance for him. The better, slightly tweaked version of the character comes to the fore and there's not a single scene where he's anything less than fine, even when bits of the material aren't. The problem – you knew there was going to be a problem – is that a fair chuck of the script is pretty rote. Harry's placed in command, it doesn't go as expected, he has a crisis of confidence, but pulls through in the end to save the day. That's all very familiar, and though laying it out bare like that does a bit of a disservice to the episode, it's hard to get away from the fact that a lot of the beats are just too overly familiar to really work. We even get a version of "but someone died on my watch!", which fine, that can be traumatic the first time it happens, but this isn't an episode with the time to burn on really exploring that. So while it's not something that's just forgotten about it's also not something given enough time to properly register and as such it can't achieve what it sets out to. It's a valid character beat but it's presented far too literally and it doesn't impact enough to carry the weight it's clearly supposed to. The predictability of this is really the worst sin the episode commits, and it's a biggie because it's undermining a lot of the solid work which would otherwise have more of chance to flourish. It's the same old Problem Of Harry – even when things seem to be going well for him there's always something lurking that gets in the way.

But even given this, I don't want to end by suggesting "Nightingale" is bad, really. It makes a real attempt to engage with the actuality of who Harry is and does more work, and more successful work, than we've seen for him in a good season and a half, and possibly much longer. It's too much to hope that one episode could course-correct over six seasons' worth of neglect and general mishandling of one character, but at least it's a positive step in the right direction, and in return we get strong performances from all involved. This week's warring aliens aren't drawn especially vividly, but neither are they a complete bust either – the blockaded planet is an interesting-in-theory development (though don't maybe examine it too closely), and if the bait-and-switch of the vaccine actually turning out to be about smuggling technology instead isn't particularly original, the script deserves points for keeping the Kraylor actually sympathetic and still on a mission of mercy, just not the one Harry thought they were on. It would have been much more clichéd if they had turned out to be the (gasp!) bad guys all along, so by keeping them on-side we at least get a slight change to the formula. OK, sure, it's not massive but at least it's something, and it's balanced by Janeway basically being taken in by the Annari. So let's on this occasion err on the side of generosity and forgive the largely obvious direction of the script in favour of giving a somewhat neglected character his little moment in the limelight. This is actually Harry's final lead in the series, he doesn't take centre stage in any more episodes, and if we come to it too late (and we do come to it too late) then let's just be glad that this his final episode and not some tedious doomed romance. Because, whatever flaws there are in this episode, we know from experience that things could be so very much worse.

Any Other Business:

• One of the great things about this episode is that it actually makes the effort to land Voyager on a planet and takes the time to show the crew repair it – we even get to see people climbing over the warp engines! It's a great touch, and again is a case of special effects enhancing, in this case, the realism of a ship in long-term deep space which requires physical maintenance.

• But while that's a vote in the plus column, in the minus column we have the whole sub-plot about Icheb mistaking B'Elanna's concern for him as romantic interest. It doesn't really serve any purpose (beyond giving B'Elanna and Icheb some lines this week) and while it's never badly acted or anything it's also a typical Star Trek B-story that contributes nothing other than five minutes of screen time.

• Though we don't get a Captain Proton scene, Harry using it as an example ("I always get to play Buster Kincaid") is a good use of the holodeck program to illustrate the point he's making, and one the character would use, so it's a decent piece of writing.

• Why does Harry have a sax with him on a stand in his ready room, when he plays the clarinet?

• Fine, so it turns out the Kraylor are smuggling a cloaking device, not medical supplies. But did it not occur to anyone to check out their story? What if they'd be running weapons or people smuggling or something?

• The most frustrating aspect of this episode remains the fact that we should have got it back in Season Two, where the more rote aspects of the script could have been forgiven if it were the start of a character arc for Harry, rather than being apologized for at the end (and I'm sure it would have been better than all that mucking about with Seska).

• Some good writing for Seven in amongst all this, with her "oh get over yourself" attitude providing a refreshing contrast to Harry's doubts.

• Which is as well, because the "mutiny" is the one part of this episode that absolutely doesn't work, never rising about cliché, and resolving waaaay to quickly to be an effective plot beat.

• Yes about that blockaded planet. Loken states that his people desperately need the cloak because the Annari are blockading their planet and they need it to get food to their people. But this is a planet, not some island with a couple of gunboats hanging off it's only port. Why can't they grow food? Are they overpopulated, was their an environmental catastrophe, is there something else? We could have done with a bit more details here to explain this.

• But it all ends on a fairly positive note for Poor Old Harry, which makes a nice change for him.

Season 7, Episode 9 / 10 - "Flesh And Blood"

Killing In The Name Of...

If "Flesh And Blood" is about anything, it's about perspective. Oh, and consequences. Oh, and responsibility. A far cry from the hollow emptiness that so dogged "Unimatrix Zero", "Flesh And Blood" roars the Voyager two-parter back into life while following up on the thematic work that's already been laid down in the season so far. Let's take stock on some of these ideas, shall we?

1) Perspective. It's everything here. And really for the first time since we've met the Hirogen we get an alternative perspective on them, which is to say we get to see a Hirogen who isn't a hunter. We get to see the consequences of involving someone rather less committed to their way of life than any other member of the Hirogen we have met, but it means we have an insider providing perspective. The Doctor fulfils this role for the holograms too – an outsider perspective on a species (if we can refer to the holograms that way) the person providing that perspective is a member of.

2) Consequences. Well this is really the centre of the non-hologram arc here. Most straightforwardly we have the consequences of Janeway giving the Hirogen the holo-technology. What they have chosen to do with it perhaps reflects what we might expect of the Hirogen – we know they're a hunting species, therefore they use the technology of the holograms to hunt. Fair enough, that was the point in giving them the technology in the first place. Yet we see a trait from Janeway here which ties in with the events of "Night" - that is to say, she apparently intentionally misremembers the events of "The Killing Game" in order to hold herself responsible and to an unattainable standard, just as in "Night" she misremembered the events of "Caretaker" to make herself seem more responsible. Here, she talks about the consequences of giving the Hirogen the holo-technology, and the danger that has put people in, apparently neglecting to remind herself that, at the end of "The Killing Game", bartering the holo-technology was the only thing that prevented the Hirogen and the crew of Voyager from slaughtering each other. So she did it to survive, in other words, rather than as a traditional trade of bargain. This is clearly part of Janeway's emotional make-up – she blames herself for the consequences of what happened, even though there was nothing else she could do. Which leads us nicely into...

3) Responsibility. This is clearly the flip-side of consequences. Janeway feels responsible for what happened because she gave away the holo-technology. The Doctor is responsible for B'Elanna's kidnapping. Donik, the Hirogen technician, is responsible for the holograms becoming more sophisticated than the hunters can deal with. What's telling in "Flesh and Blood" is that only those who face up to their responsibility and accept it are able to survive the episode. The Doctor is eventually able to admit his mistakes and move past the problems he causes. The Hirogen are able to move past their species-default of hunters to survive (well, some of them at any rate). But the person who doesn't survive – who can't survive – is Iden. He casts himself in the role of a saviour (and in this case the saviour) but is unable to accept the responsibility of that role and the weight that comes with it. As a result he is the sole hologram who doesn't make it to the closing credits. Even the Hirogen were able to overcome their instincts to hunt to the exception of all else, but given the chance to properly expand who and what he is he falls measurably short, and gets killed as a result.

So yes, there we go. Three straightforward thematic aspects all sit nicely on the surface, yet these's so very much more going on here, and in the development of these themes we start to see an emerging aspect of this season, one which was first hinted at during "Critical Care" and again in "Body And Soul", which is the way holograms are treated. In "Critical Care" the Doctor was seen as something owned, a piece of technology that was bought and sold as any other might be, though there were also - admittedly very low down in the mix - allusions to slavery in the imprisoning of someone and forcing them to work against their will (and note that in that episode people mostly treat the Doctor as someone who can be addressed as an equal, even as he's being exploited). The treatment of holograms as a rights issue is made more explicit in "Body And Soul", with the way holograms are referred to being much more directly equivalent with slavery, right up to the clichés of slavery (the whole "we even let them live in our house and they were still ungrateful!" speech that Jaryn gives the Doctor). "Flesh And Blood" (and again, note the similarity of names between these two episodes) makes this issue more explicit still, this time drawing a direct comparison with slavery rather than an allusion to it, with Iden referring to himself as a liberator of people chained by their organic creators, and of course his holy-man delusions meeting with his desire to lead the his people out of chains, as in Moses. But while "Flesh and Blood" makes the comparison with slavery explicit it also opens this up to other interpretations - the Civil Rights movement of 1960s America, the battle for gay rights, the fight for female equality – all while remaining focussed on providing a look at the schizoid dichotomy between what Iden wants to achieve (and its apparently noble goals) and his own increasingly delusional and unhinged reality. One of the things that’s become explicit over the course of Voyager is the way the Doctor functions as an emergent intelligence, and here we see the same things happening to the modified holograms the Hirogen have, with everyone treating them as basically equal to the Doctor and thus deserving of the same status and rights as the Doctor (the Voyager crew do this reflexively, and without having to have the details explained to them). Quite apart from the implicit suggestion that the Federation is on the brink of unintentionally creating potentially huge numbers of intelligences (essentially a new species), this gives weight to the moral arguments surrounding how Iden, the Hirogen and the Voyager crew see the holograms, yet we also get to see another set of holograms, who are very definitely not cut from the same emergent intelligence cloth. In a way, this feels like a curious step – since this is ostensibly about the rights of fully sentient holograms, why introduce a bunch of holograms who are not? In one sense the answer is obvious – they show the mania that Iden is succumbing to as his messiah complex takes over and he kills real sentient beings for a handful of holograms who are demonstrably not. Yet in another sense it also sets a sort of standard by which we can judge everyone else's reactions to what happens as well. By exhibiting compassion for the murdered (and entirely innocent) ship's captain that Iden kills we get to see the Doctor gradually return to the person we know rather than the convert he became, and we see the impact it has on Kegal and the other holograms. Or to put it another way – it provides a moral perspective on what's going on.

Because, as I mentioned, perspective is everything here. Almost everything exists in "Flesh and Blood" to provide perspective on something else, and those holograms are just one example which nevertheless serves to demonstrate a larger point. The obvious perspectives – the way Donik reflects an alternative perspective on what we assume Hirogans will be like, for example – help colour and shade in the details of everything that happens here, and by forcing the audience to reassess their assumptions as regards characters or motivations it means the episode can find real traction in what it's trying to deliver. Because, for all that I've said that perspective is everything, what the episode is really trying to deliver here is the fairly straightforward idea of not making assumptions and not allowing prejudice to blind decision making. That's obviously a very Star Trek theme, and by invoking a religious aspect, specifically the Bajoran religion, the episode is able to rise above some didactic lecture about how things aren't always what they seem. Indeed the profound moral ambiguity of a devout religious leader is here used as a deliberate attempt to destabilize the viewers' expectations, so while Iden starts off being a comparatively sympathetic character it's his religious zeal and fanaticism that eventually leads to his downfall. This isn't positied as a criticism of religion – again, this is extremely important to avoid the episode becoming hectoring – but is instead merely present as an example of someone so blinded by their own conceit they cannot see how far from their own path they have strayed. This is, obviously, a parallel with what the Doctor goes through, as he shifts from sympathy for the plight of the holograms, to outright convert to their cause, to Doubting Thomas (more religious parallels, then), to eventual rebel. The Doctor is, ultimately, able to maintain his sense of perspective and that eventually leads him to be true to himself and make the right call, rather than losing himself to extremism and zealotry. This paralleling of the Doctor and Iden is really the core of the episode's character work, and also delivers one of its most effective, and shocking, moments.

Because remember back in "Critical Care" I mentioned one of the key moments that the Doctor goes through is intentionally inflicting an illness on someone else, and how this essentially became the equivalent of him breaking his own Prime Directive? Well, there you could argue a bit, maybe, perhaps, if you squint a bit, that he had a moral justification for it, because he committed a small act of suffering to alleviate a much greater one. This is a slippery slope argument – the ends justify the means – but the point there wasn't whether the Doctor did the right thing or not, but rather that he was capable of doing it at all. That's fitting, since that episode stood as the functional start of the "rights of holograms" arc that's now occupied three stories this season (and will be back as the season progresses), and as "Flesh And Blood" picks up and expands on the rights theme so it also picks up and expands on what it is the Doctor is capable of. Because here he outright kills someone. There's no workaround to this – the story has spent two episodes making it clear that these holograms who have been freed from the Hirogen are people, not tools, or anomalies, or any other fudge, but sentient creatures deserving of rights and respect, and the Doctor actively guns one down. You could argue that, after beaming down to the planet with a bloody big gun, deprived of his mobile emitter, and after having basically been made out to be a fool for trusting Iden in the first place, the Doctor is pushed to a place where his actions seem, if not justifiable, then certainly not difficult to understand, but as with "Critical Care" the point here is that the Doctor is capable of doing this at all. Whatever shackles his program might once have held over him have truly been cast off now. He is free to do and act in the same way any organic might, and there's not a single reference to "ethical subroutines", which seems somewhat telling. And what he does with this freedom is kill someone (it's worth mentioning that it’s is possible to argue the Doctor didn’t know that Iden's program would be damaged beyond recovery so shooting him was a calculated risk, but that's not how it plays out on screen and Piccado essays the role as the Doctor being able to step up and take punitive action, without any excuses for his actions). This obviously gives us an entirely new perspective on the Doctor, and unlike "Critical Care" the Doctor doesn't, in the episode's final scene, try and make excuses about corrupt programming or whatever. He accepts the responsibilities for his actions, and is prepared to deal with this. Again, apart from separating him from Iden who was never prepared to face the consequences of what he did, this forces the audience to actively change the way they see the Doctor – that's why Janeway's comments at the end are more about acknowledging what it is the Doctor has gone through than it is about a more traditional sense of punishment (though if she really is going to treat the Doctor as an equal, I hope she does take away his emitter, since the Doctor is right – this would be an equivalent punishment to one of the regular crewmembers, just like we saw Tom confined to the brig during "Thirty Days"). For a character who has spent so much time being gradually whittled back to comic relief it's a bracing reminder of just what's possible with him when he's handled correctly.

The Hirogen have always been one of the most interesting and effective recurring species in the Delta Quadrant, and it's no real spoiler that this is their last big hurrah (there's going to be a lot of this over the remainder of the season, naturally). "The Killing Game" wasn't an episode that necessarily demanded a sequel, but the fact that we get one, and get to truly follow through on the consequences of both Janeway's and the Hirogen's decisions there makes "Flesh And Blood" stand out, especially since this is the only time a non-hunter is seen. Part of the reason that they remain effective is that they are not reduced to a series of clichés – we have a standard-issue growly Klingon hologram on hand in this story to show us what this can look like by way of contrast, helpfully – but rather remain cunning and, above all, intelligent. Neelix gets to do a little reverse psychology on them at the end of the second episode – what version of the story will get told? - but the point of the Beta understanding this and allowing his mind to be changed is not that he's easily manipulated by a wily Talaxian, but rather that he's smart enough to understand when it's necessary to change a point of view, when faced with compelling evidence to do so. It's not difficult to see how this feeds into the themes in the rest of the episode, but importantly by not resorting to type they Hirogen are given an additional dimension which doesn't in any way reduce their effectiveness or their status as a threat. Had this not turned out to be their final appearance the events of this episode would not in any way change the fact that they're still a dangerous, smart and cunning enemy, while still acknowledging that there's a lot more to them than just that. It's for this reason that the inclusion of Donik is so important, and why it's important that he's able to make it all the way to the closing theme tune. He's a symbol of everything this episode is trying to achieve, because just like the other Hirogen he's intelligent, capable and, like the Kaptian of "The Killing Game", blessed with enough foresight to understand that just continuing the way things have always been isn't good enough and that to survive one must change. But he's also representative of the arguments that the episode is putting forward, in a way just as much as the Doctor is. He's able to find a purpose for himself in changing, no longer a slave to the whims of an Alpha (and obviously the word slave there is chosen very deliberately) but instead able to break free and find his own path forward. Well, that's pretty clear, isn't it? In choosing to help the holograms, without coercion or favour, he comes to represent the point of this story. Just as the Doctor earns his freedom by acting in a way that demonstrates that he is capable of that freedom so Donik does the same. A thematically fulfilling, thoughtful and considerate episode, "Flesh And Blood" ultimately turns out to be the best two-parter Voyager has delivered in ages, and it certainly stands comparison against "Equinox" (truthfully, the only one to have come close to the standards set by "Year Of Hell" and "Scorpion"). As ever with these reviews there's plenty of things I've not been able to cover yet, not least of which is the fact that this, all thematic contortions aside, another absolutely fantastic entry into the action-adventure side of Voyager, and we have a production that's full of pace, energy and a real, tangible sense of threat. At this stage, in the long run up to the end of the series, it's both surprising and incredibly pleasing to have something as good as this, and something which is making real, material progress with a character when more typically we'd be expecting a greatest hits package as we get ever nearer "Endgame". There's life in the old dog yet.

Any Other Business:

• This episode was shown as a feature-length movie rather than as a two-parter over two weeks. The last story to do that was "Dark Frontier" (this is better).

• The opening sequence, with the Hirogen hunting the Starfleet holograms, and them turning the tables by opening fire from underwater, is quite brilliant. And, rather than the Garden Centre Of Doom, this is shot on location, and the difference between similar firefights ("Memorial", for example) which are studio-bound is dramatic. It's all just so much better when shot on location.

• The whole holo-ship is great, vaguely reminiscent of the one in Star Trek: Insurrection though somewhat more dangerous...

• Iden is an excellent character – a self-important, somewhat deluded person who crosses the line from sympathetic and exploited to insane, all without any eye-rolling or scenery chewing. It's a great performance too, and the character works incredibly well, especially when compared to the attempts in "Repression" to do something similar with a Bajoran religious fundamentalist.

• Equally Donik is a lovely character, and it's so great and refreshing to see another side to the Hirogen so they're not just presented as a culture with a single interest and nothing else.

• The Doctor's conversion to the cause does maybe come just a little bit too quickly, but if it does it's a very minor mistake. His trusting the shield frequencies to Iden is perhaps a bit stupid though (from a character perspective I mean, not from the writing).

• The through-line of B'Elanna's abduction and her trying to overcome her own prejudice and work with someone who looks like a Cardassian is very nicely handled, as is B'Elanna's repeated assertions about just how important engineers are. This is two intelligent, understanding female characters working their way through opposing points of view, and it makes a great counter-balance to all the testosterone sloshing about between the Hirogen, the Doctor and Iden. The thematic parallel of B'Elanna overcoming her own prejudice should also be perfectly obvious.

• Along the same lines, the inevitable praise for Roxann Dawson, who's as brilliant as ever.

• Speaking of females – we never once see a female Hirogen. I wonder how they procreate?

• The idea of Voyager hiding in the wake of the Hirogen ship is a bit daft, but it works pretty well on-screen (and with some generally terrific special effects). Though Janeway's bloody lucky there are no windows in the back of that Hirogen ship or the plan could have come crashing down very quickly.

• The Doctor killing Iden is a genuinely shocking moment, and handled really, really well on screen. Kudos to the writers for giving him the chance to go there.

• And it all ends surprisingly constructively. Donik gets a chance to undo some of the damage he's done, the holograms gain a measure of freedom, the Hirogen learn a valuable lesson, and the Doctor gets to grow as a character.