Post by Return of the Thin Olive Duke on Oct 3, 2016 8:59:15 GMT -5

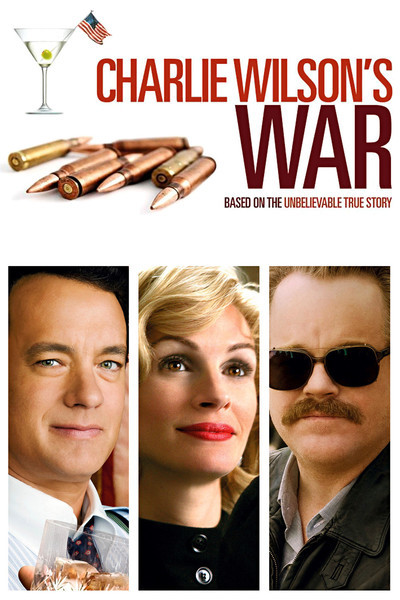

Charlie Wilson's War

Dir. Mike Nichols

Premiered December 21, 2007

To those of you who are familiar with the Cold War, or who are currently watching The Americans, the story of the Soviet War in Afghanistan and its contribution to the end of the Soviet system itself will be familiar. You will recognize the famous photographs and remember movies like Red Dawn and The Living Daylights urging western support for Afghanistan’s freedom fighters, the Mujahideen. If you’re an underinformed jackass (or film critic Bob Mondello, who read way too deeply into I Am Legend), you’re probably getting ready to tell me that we were supporting the Taliban. But what you might not know, at least not until the release of Charlie Wilson’s War, is that none of it was supposed to happen, which is what makes this story so fascinating– fun, even.

In 1980, Charlie Wilson (Tom Hanks) is a hard-partying Democratic congressman from Texas who becomes obsessed with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and particularly the U.S. government’s perplexing unwillingness to fund the Mujahideen. Turns out he has a few kindred spirits: well-connected Texas socialite/activist Joanne Herring (Julia Roberts); and CIA analyst Gust Avrakotos (Philip Seymour Hoffman), who is relegated to the meager Afghan desk after lashing out at mistreatment by his racist boss (John Slattery). On a fact-finding mission in Pakistan, Wilson not only witnesses the Afghani refugee crisis firsthand, but discovers that the Americans are deliberately ignoring the war, allowing the Afghanis to be slaughtered until the Russians hopefully run out of bullets.

Together, Wilson and Gust conspire to arm the Mujahideen. Wilson is convinced that he can raise all the money they need because he is part of the Congressional committee in charge of writing the CIA’s classified budget, and knows his efforts will go unnoticed while he’s under investigation for using cocaine. From there, and with the help of Wilson’s dedicated assistant (Amy Adams) and Amazon brigade of busty interns, they struggle to forge an agreement between the United States, Pakistan, Israel, and Egypt to give the Mujahideen the weapons they need to strike back at the Soviets.

Charlie Wilson’s War– the last film to be directed by the legendary Mike Nichols– would, in the hands of a lesser creative team, have been exactly the type of obnoxious awards-craving garbage that I have often struggled through in these final months of 2007. By all accounts, it’s still an Oscar Bait film– it’s just done by the right people. Sorkin, whose show The West Wing mined the vagaries of government for comedy as often as it did for drama, gives the film a much-needed sprinkling of levity, such as a surprisingly drawn-out scene wherein Wilson attempts to discuss covert funding with Gust but makes him leave the room over and over while his staffers alert him to the latest news concerning his latest scandal.

Tom Hanks, meanwhile, is the only actor who could conceivably have played Wilson the way he was written. Any other performance would have played him in such a way as an unintentionally repulsive corrupt chauvinist, or at best a troubled antihero. Hanks nails it, playing Wilson as he truly was: an effortlessly charming rogue with a litany of vices but a heart of gold and an iron will, and you can tell he really had fun with it. Meanwhile, Gust isn’t that far off from Philip Seymour Hoffman’s other roles in 2007, but it’s easily his most likable role of the bunch, playing the agent as a bitter do-gooder who can dish it out as well as Wilson can. Julia Roberts’ accent may be off the mark, but she too is convincing as a well-meaning if questionably motivated high society-type. Really, all the main characters are outcasts of a sort. And that’s not to mention terrific performances by any number of minor and supporting actors.

There’s no shortage of people who tell you that the freedom fighters we supported in Afghanistan went on to become the Taliban– just read the YouTube comments on the trailer. In fact this is a shameful and insulting myth perpetuated by a mixture of fashionable, third-worldist Anti-Americanism and casual racism. The Mujahideeen we supported were the Northern Alliance, the ones we put in power when the Taliban were ousted. The film knows this. It is more unapologetic for our covert war in Afghanistan than any film made since the Cold War. But it doesn’t shy away from our abandonment of the country, and the horrors that decision wrought.

In high school, I was required to read the People’s History of the United States by controversial far-left historian Howard Zinn. In an updated foreword to the book, Zinn writes that “the terrorists hate us” not for our freedoms, as conventional wisdom dictated at the time, but because we deny our freedoms to others. Now, as then, I believe Zinn was still stuck in the Cold War mindset and unable to appreciate the nature of our conflict. But in Charlie Wilson’s War there may be found a grain of truth in such statements.

Another book I read in high school, of my own choosing, was Power, Faith, and Fantasy, a comprehensive history of American involvement in the Middle East by Israeli politician Michael Oren, in which he states that the United States is the only country in the world that has, however rarely, acted beyond its own apparent self-interest. We did not act so kindly toward Afghanistan after the Cold War. By the film’s end, Wilson is a changed man, morally driven to honor our commitments to the people we helped take back their country; unfortunately, he’s the only one left.

Charlie Wilson’s War is a deceptively conventional film. The closest comparison I can think of is Ben Affleck’s Argo. But Argo was distinctive in how it juxtaposed espionage and Hollywood satire; the actions in Charlie Wilson’s War are not unusual, but merely audacious. However, the film surpasses its mundane trappings through Aaron Sorkin’s script (and let’s be glad he was working in a director’s medium this time), wonderful performances by everyone involved– big names and small– and a refreshingly sober take on the political realities of the conflict in question. And– take this as you will, I’m no isolationist– it is a cautionary tale that needs to be seen more today, in a new age of delicately shifting alliances, a resurgent Cold War, and millions of refugees fleeing unimaginable horror, than any time since its release.

Sign This Was Made in 2007

In an effort to demonstrate how far from the public mind Afghanistan was at the time, one of Wilson’s staff mistakes the country with Uzbekistan. In the 1980s, Uzbekistan was part of the Soviet Union, and no such country had ever existed.

Additional Notes

The preexisting CIA strategy, in Wilson’s words, “to have the Afghans walk into machine gun fire until the Russians run out of bullets,” is ironically a strategy famously used by the Soviet Union itself in the Second World War. For future reference: don’t be like Stalin.

Next Time: Sweeney Todd

Dir. Mike Nichols

Premiered December 21, 2007

To those of you who are familiar with the Cold War, or who are currently watching The Americans, the story of the Soviet War in Afghanistan and its contribution to the end of the Soviet system itself will be familiar. You will recognize the famous photographs and remember movies like Red Dawn and The Living Daylights urging western support for Afghanistan’s freedom fighters, the Mujahideen. If you’re an underinformed jackass (or film critic Bob Mondello, who read way too deeply into I Am Legend), you’re probably getting ready to tell me that we were supporting the Taliban. But what you might not know, at least not until the release of Charlie Wilson’s War, is that none of it was supposed to happen, which is what makes this story so fascinating– fun, even.

In 1980, Charlie Wilson (Tom Hanks) is a hard-partying Democratic congressman from Texas who becomes obsessed with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and particularly the U.S. government’s perplexing unwillingness to fund the Mujahideen. Turns out he has a few kindred spirits: well-connected Texas socialite/activist Joanne Herring (Julia Roberts); and CIA analyst Gust Avrakotos (Philip Seymour Hoffman), who is relegated to the meager Afghan desk after lashing out at mistreatment by his racist boss (John Slattery). On a fact-finding mission in Pakistan, Wilson not only witnesses the Afghani refugee crisis firsthand, but discovers that the Americans are deliberately ignoring the war, allowing the Afghanis to be slaughtered until the Russians hopefully run out of bullets.

Together, Wilson and Gust conspire to arm the Mujahideen. Wilson is convinced that he can raise all the money they need because he is part of the Congressional committee in charge of writing the CIA’s classified budget, and knows his efforts will go unnoticed while he’s under investigation for using cocaine. From there, and with the help of Wilson’s dedicated assistant (Amy Adams) and Amazon brigade of busty interns, they struggle to forge an agreement between the United States, Pakistan, Israel, and Egypt to give the Mujahideen the weapons they need to strike back at the Soviets.

Charlie Wilson’s War– the last film to be directed by the legendary Mike Nichols– would, in the hands of a lesser creative team, have been exactly the type of obnoxious awards-craving garbage that I have often struggled through in these final months of 2007. By all accounts, it’s still an Oscar Bait film– it’s just done by the right people. Sorkin, whose show The West Wing mined the vagaries of government for comedy as often as it did for drama, gives the film a much-needed sprinkling of levity, such as a surprisingly drawn-out scene wherein Wilson attempts to discuss covert funding with Gust but makes him leave the room over and over while his staffers alert him to the latest news concerning his latest scandal.

Tom Hanks, meanwhile, is the only actor who could conceivably have played Wilson the way he was written. Any other performance would have played him in such a way as an unintentionally repulsive corrupt chauvinist, or at best a troubled antihero. Hanks nails it, playing Wilson as he truly was: an effortlessly charming rogue with a litany of vices but a heart of gold and an iron will, and you can tell he really had fun with it. Meanwhile, Gust isn’t that far off from Philip Seymour Hoffman’s other roles in 2007, but it’s easily his most likable role of the bunch, playing the agent as a bitter do-gooder who can dish it out as well as Wilson can. Julia Roberts’ accent may be off the mark, but she too is convincing as a well-meaning if questionably motivated high society-type. Really, all the main characters are outcasts of a sort. And that’s not to mention terrific performances by any number of minor and supporting actors.

There’s no shortage of people who tell you that the freedom fighters we supported in Afghanistan went on to become the Taliban– just read the YouTube comments on the trailer. In fact this is a shameful and insulting myth perpetuated by a mixture of fashionable, third-worldist Anti-Americanism and casual racism. The Mujahideeen we supported were the Northern Alliance, the ones we put in power when the Taliban were ousted. The film knows this. It is more unapologetic for our covert war in Afghanistan than any film made since the Cold War. But it doesn’t shy away from our abandonment of the country, and the horrors that decision wrought.

In high school, I was required to read the People’s History of the United States by controversial far-left historian Howard Zinn. In an updated foreword to the book, Zinn writes that “the terrorists hate us” not for our freedoms, as conventional wisdom dictated at the time, but because we deny our freedoms to others. Now, as then, I believe Zinn was still stuck in the Cold War mindset and unable to appreciate the nature of our conflict. But in Charlie Wilson’s War there may be found a grain of truth in such statements.

Another book I read in high school, of my own choosing, was Power, Faith, and Fantasy, a comprehensive history of American involvement in the Middle East by Israeli politician Michael Oren, in which he states that the United States is the only country in the world that has, however rarely, acted beyond its own apparent self-interest. We did not act so kindly toward Afghanistan after the Cold War. By the film’s end, Wilson is a changed man, morally driven to honor our commitments to the people we helped take back their country; unfortunately, he’s the only one left.

Charlie Wilson’s War is a deceptively conventional film. The closest comparison I can think of is Ben Affleck’s Argo. But Argo was distinctive in how it juxtaposed espionage and Hollywood satire; the actions in Charlie Wilson’s War are not unusual, but merely audacious. However, the film surpasses its mundane trappings through Aaron Sorkin’s script (and let’s be glad he was working in a director’s medium this time), wonderful performances by everyone involved– big names and small– and a refreshingly sober take on the political realities of the conflict in question. And– take this as you will, I’m no isolationist– it is a cautionary tale that needs to be seen more today, in a new age of delicately shifting alliances, a resurgent Cold War, and millions of refugees fleeing unimaginable horror, than any time since its release.

Sign This Was Made in 2007

In an effort to demonstrate how far from the public mind Afghanistan was at the time, one of Wilson’s staff mistakes the country with Uzbekistan. In the 1980s, Uzbekistan was part of the Soviet Union, and no such country had ever existed.

Additional Notes

The preexisting CIA strategy, in Wilson’s words, “to have the Afghans walk into machine gun fire until the Russians run out of bullets,” is ironically a strategy famously used by the Soviet Union itself in the Second World War. For future reference: don’t be like Stalin.

Next Time: Sweeney Todd